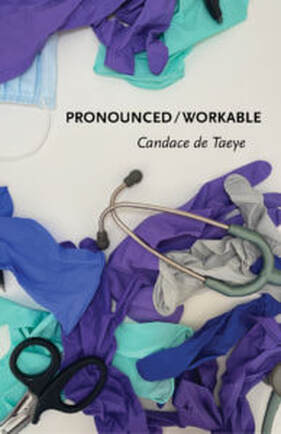

Candace de Taeye's Pronounced / WorkableReviewed by Zane Koss

I often wonder, as a poet and scholar of poetry, how we translate the raw data of experience into language. It’s an everyday operation that most people seem able to accomplish without the degree of uncertainty it causes in my own head. Even as we shape our experiences into language, those experiences are already shaped by the language available to describe it before the experience is able to enter our consciousness. How is it possible to communicate anything without falling into a wormhole of linguistic vertigo, ouroboros-style? It’s turtles all the way down. Given this chiasmus, we might wonder how the conditions under which we live our lives—the personal, cultural, and historical specificity that marks what we each individually understand as “the world”—shapes the language available to understand that world. Candace de Taeye’s Pronounced / Workable takes up this question from the perspective of a paramedic who has worked in the Greater Toronto Area for nearly two decades. These are poems written in the interstitial time between calls, often from the passenger seat of an ambulance, as de Taeye admits in a brief essay as part of rob mclennan’s on-going series, “my (small press) writing day.” As she puts it there, referencing Virginia Woolf’s seminal essay, “I do not have a room of one’s own. I usually write in an ambulance.”

Though the poems operate through a variety of forms and modes, they share a common allegiance to syntactic economy. Across many of the poems, this formal commitment telegraphs a sense of urgency—the clipped speech of First Responders with a deeply formed relationship, where an extra word might delay a life saving procedure, and both workers have been through enough together to be able communicate without speaking, in any case. In the aptly titled “Taking Action,” the second piece of the triptych “The Lay-Hero Archetype and the Public Access Defibrillator,” for example, de Taeye recounts a response to a cardiac event in clipped sentences and sentence fragments: “Rich deep descriptions of the colour blue. / Cyanosis, convulsions, incontinence. Strengthen / trustworthiness. Iteratively agonal respirations are / misinterpreted. Fixate on victim’s face” (22). Usefully, for the poet’s purposes, this fragmented, terse syntax also calls forth a long history—or, better, lineage—of avant-garde poetics from Gertrude Stein to NourbeSe Philip. Here, the clipped speech of paramedics’ labour torques the language of everyday life into a challenging deconstruction of sense and sound in line with the past century of experimental writing, yet grounded in labour and exhaustion equally as much as critical theory or the avant-garde. That the impetus for this poetic difficulty lies within the lived experience of the conditions of work only underlines its honesty and authenticity. Yet, this terse fragmentation also points in other directions. The poems in de Taeye’s book concern trauma, both mental and bodily. We can locate this trauma both in de Taeye’s patients’ bodies and her own. There is something about the eluded words and fragmented sentences that points to the unspeakable nature of much of what de Taeye chronicles through this account of her working life. One poem, for example, crosses between two techniques of contemporary experimental poetry: digitally generated writing and translingual migrations. The poem itself, in effect, speaks to the question of how to deliver medical advice or life-altering information when you and a patient don’t share a language. In our contemporary world, such communications occur with the help of digital tools like Google Translate. Yet the poem leaves us with the haunting lines “Your husband died / many hours ago / I am so sorry” alongside their Google-powered translation into Korean. So much cannot be said in either language, and de Taeye is interested in what happens within that gap, and how technology only widens that gap even as it tries to bridge it. The centerpiece of the book is the poem “Accumulation,” told in six pages of enjambed couplets before fracturing into a haunting single line that repeats six times at the poem’s close. True to the title, the poem works half by accumulation, building force through the sheer number of incidents that the poem records, but also half through jarring and restless shifts. Throughout the poem, de Taeye continuously pulls the rug out from under the reader. Each time you think you’ve sorted out the details of a narrative fragment and began to understand the traumatic incident the poem relates, the poem swerves, adding new and disturbing details that slap the reader back into consciousness, trying to understand what traumatic situation de Taeye has newly embedded us into. It’s an astonishing poem—a technical feat that lands repeated emotional blows, a vivid marriage of experimental form and affecting content that marks one high point for what Pronounced / Workable seeks to accomplish. The books climaxes with “Isolation Rooms,” a series circularly linked sonnets—a broken crown—that chronicles life during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic as a paramedic, parent, and partner, or as de Taeye puts it in the eleventh poem of the cycle, “To the Poets,” a “Fragmentary language / crown attempts to wed the historical / record” (96). De Taeye elegantly uses the form to capture both the haunting yet fleeting moments of the pandemic and the sensation of being stuck in time that accompanied the experience of recurring waves and lockdowns. As she writes in “To the Poets,” “The pandemic is a constraint / in fourteen lines” (96). Both of these longer poems work effectively to use form as a means of understanding and conveying their content to the reader as an experience that the reader, like the writer, must undergo. Pronounced / Workable represents a cumulative achievement for de Taeye, both aesthetically and in terms of the poems collected in the volume, a couple of which date back to 2015. I know this because (full disclosure) Candace was a founding member of &, Collective, a poetry workshop I organized with Mike Chaulk in Guelph, Ontario and that lasted more-or-less from 2014 to 2016. Candace was a key member of that group, a load-bearing column who—despite work and life commitments that far outweighed the other, younger group members, nonetheless—acted as a driving force through her consistent, focused, and professional writing practice. Since then, de Taeye has been quietly prolific, releasing poetry in several collections—some self-published with &, Collective as well as with Publication Studio Guelph and Vocamus Press, a local Guelph mainstay—as well as a paramedic’s guide to fast and cheap dining in Toronto, The Trashpanda Medic’s Take-Out Guide. (Modestly, the biographic information provided at the back of Pronounced / Workable downplays or elides some of this previous work.) Throughout this time, de Taeye’s writing has demonstrated a sense of intellectual rigor and curiosity even as it has maintained its urgency, tackling topics from childbirth to grief with a restless pursuit of poetic innovation. That remains true in Pronounced/Workable, and it’s a pleasure to see de Taeye playing with such a wide variety of poetic forms and fitting each to her concerns in this collection: the nature of work, death, trauma, exhaustion, and life. It’s a tough book—strong and difficult—and demands your attention. Zane Koss is a poet and translator from Invermere, B.C., living in Guelph, ON. He is the author of Harbour Grids (Invisible Publishing, 2022) and co-translator of Hugo García Manríquez’s Commonplace (Cardboard House, 2022), as a member of the North American Free Translation Agreement (aka NAFTA). A second book of poetry, Country Music, is forthcoming with Invisible Publishing in spring 2025, and a second collaborative translation, of Karen Villeda's String Theory, will be published by Cardboard House in fall 2024.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us