Aaron Schneider Interviews Andrew Wenaus

Aaron Schneider: What’s the origin of this play? Why did you write it? Where is it coming from and what tradition do you see it fitting into/breaking with?

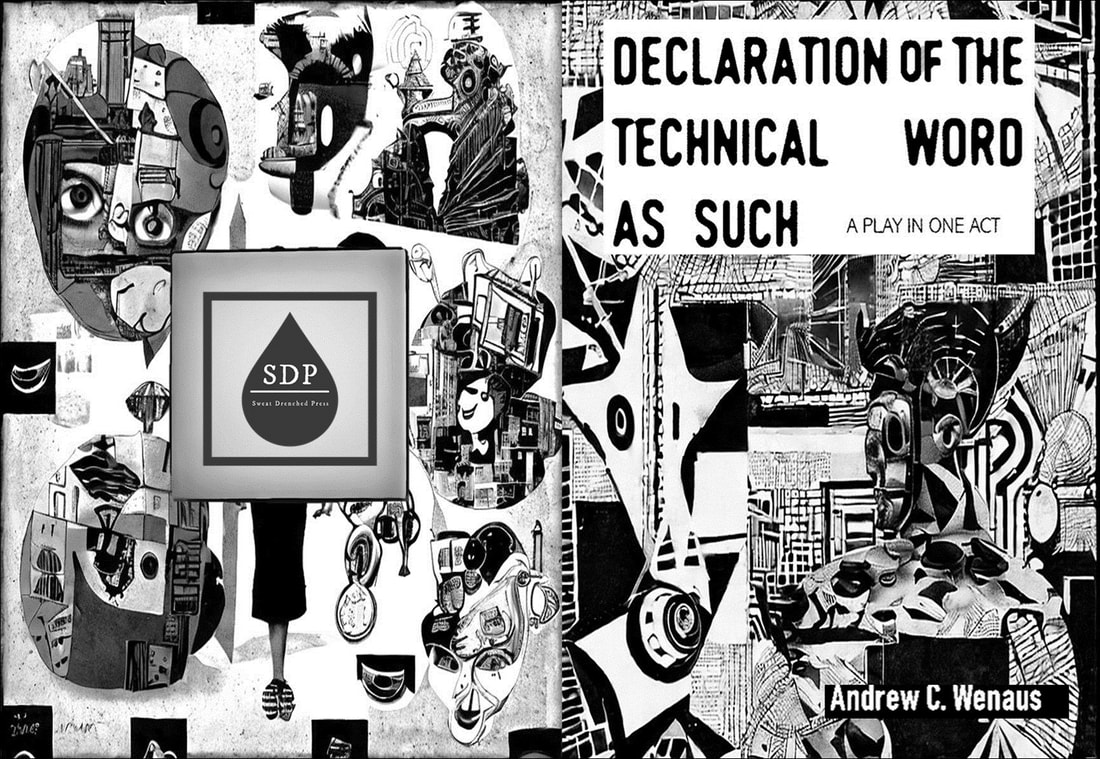

Andrew Wenaus: Many thanks for taking the time to ask me some questions about Declaration of the Technical Word as Such. I’m a bit unsure of the origin of the play, to be honest. As flaky as this sounds, I tend to think about things, have those thoughts stew in the back of my mind, then suddenly an idea or merger of disparate ideas come together and appear to me almost fully formed (for example, I wrote this play in about 48 hours and then spent a week editing it). That’s, in a way, how this play came about. I’d been working on a number of things and two merged: the first was a play where characters would enter the stage, begin reciting their lines, die, while, without losing a beat, another actor walked on-stage to continue the line. This idea merged with a second idea for a manifesto that revisits a short, but influential, 1913 essay by the Russian Cubo-Futurists Velimir Khlebnikov and Alexei Kruchenykh: “Declaration of the Word as Such.” Basically, in their essay, they make a claim that a poem can be built around a single word. Not a one-word poem, but a poem that uses etymological mutations and word histories to build a poem around. Khlebnikov’s poem “Incantation by Laughter” is the go-to example. It is nearly impossible to translate into English; the translation in the link captures the content fairly well, however there are other translations that sound a bit like someone trying to recite a poem while laughing uncontrollably. The original Russian captures both. In English literature, James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1933) would be the closest linguistic experiment. Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh’s approach to poetry would soon after split in two directions: Kruchenykh in the direction of a paradoxical personal and universal articulation (largely inspired by shamans speaking in tongues) while Khlebnikov, who is sometimes better studied by mathematicians and linguists than by poets, moved in a direction of etymology, symbolic logic, mathematics (particularly nonlinear mathematics). Khlebnikov had a massive influence on linguistics, inspiring Roman Jakobson (who ran in the same circles as Khlebnikov in his youth), calling the poet "the greatest world poet of our century" and “the king of poetry.” I wonder, what would a “word as such” mean in the 21st century when words are almost exclusively technologically mediated and Khlebnikov’s theory of language proved to be prophetic? What the Russian Cubo-Futurists were hoping to accomplish was quite literally the opposite of the Italian Futurists. While the Italian Futurists are perhaps best remembered for their fascism, misogyny, worship of violence and war, and their obsession with speed and mechanical artifice, the Russian Cubo-Futurists—at least in the realm of poetry—had a central mission: to expand the parameters of language by, frankly, creating endless new words. Their project would be oppressed by Stalin’s idiotic censoring of all experimental arts in favour of Socialist Realism. As a result, the prerogative of the Cubo-Futurists largely went underground. In a way, I’m not so much breaking with a tradition here as revisiting on that was forced into dormancy. Cubo-futurism had a revolutionary understanding of language from before the revolution turned sour; but, like all iconoclastic Modernisms it sought to create a new language and new concepts for a radically different way of living and organizing society. Because the modernist experiment, like most revolutionary experiments of the 20th century, never fully materialized, we basically still think, act, organize, behave, write, and read like Victorians. I’m fully convinced that we almost became modern a few times during the twentieth century; each time was thwarted by systems of control whose geopolitical function is to standardize, repeat, and establish homeostasis in a near-infinitely complex set of relations…the purpose of that homeostasis, however, is to manage the circulation of objects and concepts in the favour of those in control. So, I tend to revisit the high-experimentalism of the early- to mid-20th century simply because it feels like, despite everything horrendous and astounding that took place, we’re cognitively and artistically still living in the 1800s. This is why I wrote the play. AS: You reference Velimir Khlebnikov. Can you talk a little bit about who they were and their influence on the play? AW: In a lot of ways, the play is part of an attempt to both revive Khlebnikov’s approach to poetry and language while also bringing him to the attention of English language readers. I think the American poet Andrew Joron—who has been called “the American Khlebnikov” which he isn’t, he’s the American Joron, which is a poetic force in itself—has already been doing this for decades. But, with the resurgence of interest in a number of pre-revolutionary, but specifically anti-bourgeois forms of art and science originating in Russia—Russian Cosmism and Cubo-Futurism, in particular—I think it is also timely for us to think about Khlebnikov more seriously. In a way, Khlebnikov could’ve been as influential on English language poetry as Pound, Eliot, or Cummings; had he been, I think we’d be better equipped for the late-twentieth and early twentieth centuries. Why? Simply that Khlebnikov’s mathematical approaches to language has a lot in common with the way that digital code operates. Even the tiniest change in coding script will make a procedure work, or not: a coded algorithm could generate permutations on a corpus of data ad inifinitum while also eliciting novelty. ChatGPT and programs like Midjourney basically work this way but, again, its special language (the processual coding functions and operations that operate endlessly behind the interface) remains invisible to all of us other than coders. When Khlebnikov makes bold statements along the lines of a change in a single letter does not simply change a word, it changes the world (i.e., the inclusion or exclusion of the letter “l”), he envisioned a poetry of language that affects reality itself: a kind of strange merger of magic and mathematics (which is pretty typical of many late 19th century Russian writers and artists). Digital code as we understand it now did not exist during Khlebnikov’s short lifetime but if we think about his vision from the vantage point of the twenty-first century we might be surprised that we indeed do have a language (a highly technical one based on calculation and executable proceduralism) that, when a single glyph is changed, a radical change takes place to the system in which it finds itself (the aggregate of other executable processes). Khlebnikov dreamed of a language that would do this to material reality. The goal for him was simply to “re-discover” a kind of Adamic language or even the original utterance that brought the world into existence (according to the Judeo-Christian tradition to which he belonged) and to build perfectly from there. Certainly, we can mostly all agree that poetry elicits change. But that change is cognitive which can then be turned social, political, spiritual, destructive, idiotic, narcissistic, or whatever…it can be turned into something good or bad. But, the poetry itself doesn’t change the world. It’s the behaviour of people who’ve read the poetry (or engaged in art) who make the change. Khlebnikov dreamed of a language that could do this in itself: somewhere between a call to social action and a literalization of the goal of magic. While magicians don’t have the best track record of actually affecting the reality of the system around them (instead, they are the masters of illusion), digital code does. This is why, to revisit a part of the first question that I didn’t really answer, I titled my play the “Declaration of the technical Word as Such.” The “technical” here is a reference to Vilém Flusser’s idea of the technical image: the significance of a photograph isn’t its content but the scientific, material, chemical, and, later, digital apparatuses that make it possible. In other words, Flusser simply wants us to remember that we need to consider the “black box”—the invisible chemical changes or digital “beep boops” that take place behind what we see when we use technology—when we think about media. So, what could this mean to something like poetry? It may seem like the answer is “nothing at all.” But, the “black box” of technology is only made possible by those who created the system. Those who know coding do not think about ChatGPT or Midjourney as magic; the programs are predictive and combinatorial, the aggregates of embedded procedures. Having knowledge of code and calculation gives an individual certain special access to 21st century communications in a similar way to how a grimoire gives special power to the magician in fantasy narratives. Is it possible that, by treating or at least so much as acknowledging code with the same poietic intentions as poetry, could we begin to radically change the world through art that stops talking about technology and, instead, fully merge with the actual languages of digital technology itself? Anyone who doesn’t identify as a creative or an artist has this tremendous feeling of emancipation when they use ChatGPT or Midjourney simply because their thought (or familiar linguistic prompt) became a reality. But, those realities are, despite the apparent limitlessness, intensely regulated and delimited by a program that reproduces the values of those who wrote the source code. Imagine the mass sense of liberation if everyday people were educated in both art and source code: what if we, not private corporations with profit motives, were the owners and authors of the mediums of communication and production well beyond the basic AI tools today and could be the authors of our own future? I think a serious reconsideration about what language is, does, and can do through the lens of Khlebnikov’s theories of poetry is a step in the right direction for us, en masse, reconsidering that we can also use code rather than simply be used by it. Given the strange, friendly-looking surveillance state in which we currently live, I sometimes think of so much creative writing today is seeking homeostasis with the system that ironically represses it. The irony being that the apparatus standardizes limits to what constitutes an authentic self, the self then articulates itself back to the apparatus, thus confirming that which the apparatus sanctions as true; consequently, so much poetic and artistic empowerment today, despite the way it looks and feels on the surface, may also be considered an offering to the source of subjugation. I suppose this process has always been the case; today it is simply algorithmically intensified and, unlike an artist working for an influential patron, we mistakenly think we are honouring ourselves rather than honouring the control mechanisms of a technological system of power. Khlebnikov helps us “off load” the self in the service of that which will long-outlive us and transcend the categorical limits the apparatus places on us. Empowering and liberating art, like empowering and liberating ideas, will nearly always be met with resistance, even riots; if it’s met with enthusiastic approval, I typically remain suspicious. If anything, we need to focus more on form in the service of content just like we need to learn how to ask the right questions rather than seeking to find the right answer. But, reasoning in the midst of a feedback loop isn’t all that easy, and perhaps the chicken and the egg are one and the same after all. AS: There is an interesting contrast between the philosophical abstraction of the dialogue and the materiality of the production you envision. The Prologue has male and female body builders striking poses while making pronouncements that are more at home in a theory seminar than a body building show. It’s a fascinating collision of worlds. How do you see this contrast operating in the play? Why draw these particular worlds together in this way? AW: Thanks – this was precisely the effect of the juxtaposition I was aiming for: an intellectually abstract manifesto of a sort being presented as a slapstick routine or carnival act. In fact, much of the strangeness of the play—injury and death without pathos, acrobats, impractically difficult feats of strength, etc.—may be a bit more explicable if one were to imagine it in the tradition of the carnival, folk theatre, or vaudeville. And, while I really do not like talking about myself because it is painfully uninteresting, I think that juxtaposition captures my personality: I see, and have always seen, the world as a high theory slapstick routine – existence is a comedy. I do not mean this in a pessimistic way; instead, it is liberating because collective laughter is revelatory and an affirmation of friendship. The theatre of Samuel Beckett or Eugene Ionesco is part of the same trajectory as Dante’s great teleological comedy. The play Victory over the Sun—composed collaboratively by Kruchenykh, Khlebnikov, Mikhail Matyushin, and Kazimir Malevich and premiered in 1913—is also a comedy and was the inspiration for the body builders. Victory over the Sun opens with two strongmen ripping down the stage curtain. I thought of the body builders as a pair of ringmasters: they welcome you to the circus and introduce the “impossible” feats that the audience will witness. Their hyperbolic embodiedness (steroidally big muscles, artificially defined contours through spray tans, the bodies as spectacular surfaces, their existence as absolute performance) contrasts with the numerous and simplistically binary permutations of Man and Woman in the play who struggle but collectively and actually give the articulation (the binary here is meant to operate as a red herring: it really seems at first as if it is a comment about gender, but the nature of the play, as it progresses, makes it more likely that the two bodybuilders are an analogue to the infinite permutations made possible by binary code…again, reminding us that computer code and human beings are radically different yet both agents of change and mutation). The bodybuilders, whatever they are, are a medium. Unless you’re face-to-face with someone, our communications today are made possible through massively complex technological procedures and calculations that continue to function and operate even when we aren’t communicating. Whether we are having a conversation with our lover, a dear friend, or our family, if it is happening through any technological medium, it is subject to the processualism of a digital apparatus at the most foundational level: form (not emotion or content). So, today there is a tendency to become obsessed with our own self-representation through the surfaces, rather than through less immediately categorizable modes of significance. Whether we think of it or not, when we want to influence others in line with our cultural, social, or personal values, we are frequently unconsciously also aiming to influence the algorithms of media communications technologies that will mediate that act of persuasion. So, to a human being things like language, culture, and history are typically deeply meaningful things; but to a digital algorithm, these things are a corpus of data to be accessed, reorganized, and optimized in ways that will stabilize the system of control in which the user maintains the experience of being in control while being subtly steered in limited, pre-ordained directions that benefit the owner of that algorithm. It’s a tough pill to swallow; but the research shows that we are shaped by these algorithms and those algorithms can shape, steer, and predict us in ways that have been shown to be so terrifying that they’ve basically been repressed: “let’s pretend we didn’t hear that….it is too horrifying to consider.” Whether the bodybuilders are a hilarious (at least I find hyperbole hilarious) kind of metaphor for what the technical word could bring about (they are the “ring masters” after all) or whether they are the apparatus (repressive, a metaphor of ridiculous power) has no answer. I wanted those contradictions to oscillate in their value. The reason is that there isn’t an answer to whether they represent liberation or subjugation. Simply put, the apparent incompatibility between materiality and abstraction is meant to generate a state of questioning: if it is both and neither, then we need to think harder and, in a way, the poiesis of the art’s formal chiaroscuro—not simply the content—transfers to the audience. In fact, you can’t really have abstraction without drawing attention specifically to the material: after all, how can something be abstract if it has not been ab (drawn) tracted (dragged, removed) from something that has material existence. The abstract can change the material, and this is the lesson of the past 80 years, because abstractions are in the intellectual and commercial ownership of who and what actually governs and manages the modern world. Also, if you hang out enough with literary or cultural theorists, you sometimes do feel like you’ve stumbled into a WWE match. Even more simply, I find the hard contrasts and hyperboles hilarious modes of disrupting polite expectations. Slapstick, with its impossibilities and exaggerations, is a big “yes, we just did” in the face of middle-class manners. There are truths and deep pathos that Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati, Margaret Dumont, or Mel Brooks articulated that couldn’t have been expressed in any other way, and they do so by laughter that brings feelings of humility, collectivity and comradeship while also mocking both themselves, established conventions, and power. The first great play of the 21st century, Cliff Cardinal’s The Land Acknowledgement, or As You Like It (2023), is a masterpiece for this reason. AS: This is a play, but its stage directions render it close to if not impossible to produce. For example, each character dies after making their declaration and is replaced by a new character who makes their declaration, dies, and so on. As the end of the first act approaches, there are, by my count, close to 100 bodies littering the stage. You then have a posse of acrobats enter and form the shapes of a series of quite complex patamathematical poems. It’s a moment that is as funny as it is conceptually sophisticated, and it works in part because of the total impossibility of what the stage directions describe. Why did you choose to write this as a play? How do you see the tension between the performativity of the dialogue that is made up primarily of pronouncements and the impossibility of performing the script operating in the play? And, more broadly, why chose to simultaneously invoke and refuse performance in this manner? AW: I wrote it as a play for the same reason Eugene Ionesco said he wrote for the theatre: it could not be articulated in any other way. I’m also a little familiar with the theatre, having worked as a composer, musician, and sound designer on and off over the years. But in no way am I a “man of the theatre,” and often feel very much alienated and baffled when talking with people who are enthusiastically involved in theatre and musicals. I’m typically happier reading and studying specific kinds of plays (symbolist theatre, Dada performance, theatre of the absurd, miming and clowning, and ritual plays) than going to a theatre. Its an odd choice for me, the theatre, because I am generally unhappy and uncomfortable around actors – their empathic engagement feels intrusive in my experience; I prefer working with dancers because their empathy has a kindness and a communicativeness. That’s unfair, I know, but so are all personal preferences. But why would I write it as a play when so much of it would be nearly impossible, if not impossible, to bring to the stage? Well, on the one hand, reading a play requires a great deal of work from the reader – we must bring all the details to life in our imaginations in order for this fragmented document to make any sense whatsoever. So, in a way, a play script is a mode that encourages, even forces, creativity explicitly at the level of reading. But I also wrote it as a play because everything artistically worthwhile should seem impossible. While certainly a direct translation of the play into performance would be impossible (the acrobats), most of it could be intimated. I would be interested to see what a troupe or company might do with something like this. But part of its impossibility is simply that, because you can write whatever you want in a script, then do whatever you want as a challenge to yourself and others. Theatre requires lots of people coming together – so, what would be done would be the decision of the director, cast, and crew. I say: let’s make it possible. I want the impossibilities to be funny. When we’re laughing at an impossibility, at least we’re acknowledging limits; when we identify limits, we can then at least start planning on how to breach them. So rather than despair, I hope it elicits laughter and laughter’s attendant “fuck you” to power and its great love and understanding for everyone else. Maybe it’s a bit of a refusal to confirm what is familiar in favour of that which affirms alien potentialities. In fact, if the play is performed, I hope it undergoes all kinds of permutations. Finally, I have been accused of being hostile to the theatre to which my response is “those who wish to transform the theatre aren’t hostile to it.” If I’m feeling particularly vicious and prickly—as I do today since I am writing on the very sad day the great filmmaker Kenneth Anger died—I may remind those who hold this attitude of dismissal towards experimentalism that their soft-censorship of intrepid art is perfectly consistent with the hard-censorship of totalitarians and dictators. The future, for me, should be ludic but not escapist entertainment or middle-class self-confirmation in the disguise of neoliberal empowerment narrative; instead, it should be inaugurated by entertaining endless, ineffable artistic potencies toward the establishment of yet-imagined possibilities. I want high concepts to be as fun and inviting as they are apparently difficult and inscrutable. I legitimately do want to see something like A Thousand Plateaus: ON ICE! or, say, Kurt Gödel's "On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems I: THE MUSICAL." To those who say that these things are impossible, I say “admit it: everything is impossible, and yet here it is.” AS: The script is bracketed by a pair of columns that contain text, numbers, and formula. The font is faint, but readable. Can you talk about why you added this detail to the script? How do you see it interacting with the central column or core elements of the script? And, finally, how do you see this recalcitrantly textual element operating within a work that is, at least in so far as it is identified as a play, oriented towards performance? AW: The columns are, in fact, the text of the play itself expressed according to the source code that makes “word processing” possible. The columns, alien as they seem, are the same content (not similar like a translation, but the same) as the play; the only difference is the formal grounding of the language being used. So, while we click on our computer keys, and a corresponding glyph appears on the screen, we should remind ourselves that this is not what it seems. What do I mean? Well, when we use a pen, our hand moves a material object that spreads a material (ink) on another material (surface); when we click on a typewriter, we’re using force to move a hammer, that then transfers ink to paper. It is a very immediate, intuitive, and concrete experience; with word processing, things are much more abstract. When we click on a key, an information signal is sent that affects an information receiver: this is all invisible and is made possible by hugely non intuitive, complex calculations that are executed by an otherwise everyday program. What we touch and what we see is made possible by that which cannot be touched nor seen. The source code exists in the black box of the program. What we see, however, is the interface: a visual display that hides the programming, giving the illusion of our direct interaction with communications technology. That coding, and the information procedures that make word processing possible, are invisible, non intuitive, and abstract to the point of being a non-experience. What makes word processing possible is kept hidden for the sake of ease of functionality; however, anyone who’s run into computer problems soon finds out that, unlike sharpening a pencil or applying a new ink ribbon to a typewriter, we don’t know how to fix, let alone, actually manipulate this tool. So, you have a repetition of the same information expressed with different semiotics: the source code as columns, holds up the architecture of the illusion. The “columns” could remain completely absent from a performance of a play, and their very absence could help make this point: it’s officially there but remains invisible. Why its absence, we might ask? Why would a director, with their position of power, deny us this? Alternatively, I can also imagine it running on a screen like a set of data. But, again, if the columns provoke a reader to ask questions, then it was a success. If someone has read the play and sees a performance where the columns are not so much as even addressed, their protest would also get the point: make the source of control available to the audience and, by extension, everyone. It is also a way for me to literalize the phrase—coined by N. Katherine Hayles—“word processing is world processing”: this, to me, seems like a confirmation of Khlebnikov’s goal for language. AS: One of the things that I found most striking about this was its preoccupation with the intersection of materiality and mortality, particularly as it is located in the body. In the Prologue, the male and female body builders take out reading glasses to read their lines off of recipe cards, suggesting an incipient decay. And, as I have already observed, by the end of Act 1, the stage is littered with bodies. Can you talk about your interest in materiality and mortality in the context of the ideas you are engaging in the play? Why bring this particular focus on the body and death to this material? AW: There’s a lot that I could say here, so I’ll try to start with where the idea of all the death came from. Because I find a lot of theatre really annoying and am not very happy around actors, I vaguely remember having this idea of a cartoonish nightmare situation where you’re watching the most inane, taking-it-self-so-seriously play where the actors are there to be seen rather than there to be the egoless mediums of the piece, and you (as an audience member) suddenly are blessed with a lever that would drop the actor into a pit (of lions, why not…it’s not real) and they’d be replaced with another actor until the play was worth watching. You’ve been given this power, but you keep just getting more of the same making your own cruelty turn full circle. A kind of Looney Tunes-esque karma all around. I then started working on a play about suicide inspired by Herman Berger’s Tractatus Logico-Suicidalis and John Donne’s Biathanatos where I might use this trope: a collective monologue that would persist regardless of those who disappeared before an audience that doesn’t want to hear any more and wishes to retreat into denialism. But, that idea turned into something else that remains incomplete called Billy Watson, Mon Amour (Billy Watson was a vaudeville actor who popularized, if not invented, the slipping on a banana peel gag – Billy Watson, Mon Amour is now a dialogue play between Billy Watson, who wants to end his life, and a banana peel who refuses to be stepped on). I then thought of the ways that digital information (not the content, but the processes that make it possible) persists in ways very differently and very similar than material existence. The differences are too numerous to list, so we’ll just say that there are more differences than similarities. The one similarity that digital information and the body most certainly do share is entropy. The fading (or light-grey) ink used for the source-code columns is informational entropy. The bodies on the stage are material entropy. The bodybuilders, yes, need eyeglasses; physical hubris, sure, but also that, regardless of whether to the audience they are represented as analogues to the power of digital apparatus or what humans could become if they had knowledge and access to the digital apparatus, entropy still applies. Entropy is basically decay; however, in information theory, this decay is both a blessing and a curse. It is a curse when noise over comes a signal that one really wants the receiver to gain access (“can you hear me now?”). It is a blessing because, in information theory, information is asemic: it does not mean anything but is a kind of abstract medium for…whatever, really. However, entropy and noise in an information system means more possibilities and more potencies. A received signal/act of communication over an electronic network, without interference, will have near-perfect fidelity to the original signal. With the interference of noise, however, what is received becomes open to possibility. Are the men and women in the play dying mid-sentence because they are focused on content rather than form and, thus, being used and discarded by a system that is in the process of operating? Or, alternatively, are they expressive of a persistence for new modes of articulation that cannot be achieved by an individual or a single generation? Everything is subjected to entropy; everyone, with the exception of Keith Richards apparently, dies; so too do all systems of control. We could say that the only constant is change, but I prefer the phrase “the certain truth of actuality is the persistence of blossoming potencies.” Noise and entropy are unpredictable, but fecund. Our certain and eventual execution by the universe is also an affirmation that all the shit we deal with, all the humiliation, narcissistic individualism, hopelessness, subjugation, all our sorrow and defeat will fade into, not nothing, but something new and unimaginable. Whether are attempts at declaring ourselves are absurd or whether they are warm offerings to the next in line, we can always find solace in the fact that things will change. In fact, if we collectively exorcise four horribly unproductive ways of thinking that pervade the arts today—personal expression as marketability, the belief in “authenticity,” the need for ideological confirmation, and obsession with unimaginative dystopias—I think we’d be ready to start becoming modern. I see these tendencies as instances of normalized self-subjugation to the benefit of those who have access and ownership of the digital apparatus. In fact, the first three are largely responsible for the failure of imagination that dwells on dystopian thinking and feel like, rather than a warning, a confirmation that we are ill-equipped to so much as consider utopia. Today, being dystopian is cool; and being utopia is uncool. How is this not internalized infantilization? It reeks of the logic of boneheaded schoolyard bullies. Once we admit that we collectively can change, then we’ll be able to do so; but, utopia cannot be micro-managed or engineered. It will emerge from the complex dynamic system of aggregate individuals starting to become aware of itself as an entity that, despite entropy, persists through change. Aaron Schneider is a Founding Editor at The /tƐmz/ Review, the publisher at the chapbook press 845 Press, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Writing Studies at Western University. His stories have appeared in The Danforth Review, Filling Station, The Puritan, Hamilton Arts and Letters, Pro-Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, BULL, Long Con, The Malahat Review and The Windsor Review. His stories have been nominated for The Journey Prize and The Pushcart Prize. His novella, Grass-Fed (Quattro Books), was published in Fall 2018. His collection of experimental short fiction, What We Think We Know (Gordon Hill Press), was published in Fall 2021. The Supply Chain (Crowsnest Books) is his first novel.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us