Interview with Roxanna Bennett and Jeremy Luke HillInterview conducted by Kevin Heslop

|

|

This conversation took place on 26 September, 2019. The transcript has been edited for clarity.

I wonder if we could begin by talking about orthodoxy and divergence. Luke, what about publishing orthodoxy are you consciously shucking and what are you intentionally inheriting with this new press?

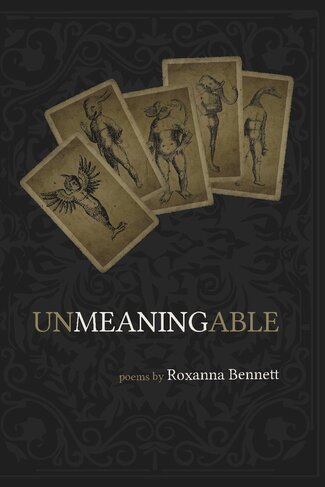

Jeremy Luke Hill: So, we’ve sort of gone looking for non-orthodox writing. Especially when it comes to fiction and non-fiction, we’re looking for things that are a little bit off the beaten path. But we’re also looking for people poetically who are willing to experiment with form––which is more Shane Neilson’s area than mine. And part of that is really deliberate in the sense that––this is gonna sound bad, maybe, but––if you’re already not trying to fund yourself, why not take on more interesting projects. We’re not gonna sell thousands of copies and be Doubleday anyway. We’re already operating in a market where we’re gonna survive on government funding and people donating and being in that mode. We’re able to do things that aren’t dependent on having to sell a thousand copies. Mm. JLH: You talk to some small publishers, and it seems like they’re still playing that game: if I could only get a book that hits the book club market, we’ll make money that way. And I feel like if you’re gonna be in that market, be in that market. Find the things that are interesting. Find the things that are strange. Find the things that are talking. Find the things that are dealing with issues that aren’t really being dealt with, and then roll with that––because those are things that won’t get picked up otherwise. So there’s almost a little bit of perversity there. But also, I feel like those are usually the things that resonate with me most. I read a lot of CanLit, and I’m not picking on anybody, but a lot of the time I feel like what comes through that pipeline is not bad writing, but it’s very much the same writing. And that comes from an increasing professionalization of writing where everybody’s got an MFA and--I’ve got no problems with MFAs, but--there’s that kind of professionalization that results in a sameness of writing. And at some point, I want to read something different, something interesting that knocks my socks off. And there are people out there doing that, and that’s kind of where we want to be. So, speaking of MFA programs, or post-secondary education generally, Roxanna, I know that you studied and dropped out of the Experimental Arts Program at OCAD. Roxanna Bennett: I did. And I wonder whether you felt that sameness was being encouraged at that institution or at schools in general––whether they resist a sort of originating creative impulse. RB: School in general, I think, has that effect of sameness. I mean, school as we have it here in Ontario is really just training us to go to work at whatever jobs the province has an agenda for. So, it’s training to be a good cog in the machine, I think––a lot of it. That’s not to say that there aren’t wonderful teachers and wonderful subjects, but systematic education I think discourages individuality and diversity, and institutions do that, I feel. You asked me about OCAD? I did. RB: I went there before it was OCAD; it was OCA, so it was still a little less of a formal institution than it is now. It was part of the university system, so there was still a sort of hangover from back in––it was part of the Rochdale Institute, back in the day. So it was still a little more experimental when I went there. But it was definitely … not what I expected of an artistic institution. I have a problem with visual art teachers who ask you to explain the project they gave you. Especially something like colour theory, where it’s like, Paint blue. We want you to paint blue. And you paint blue. Blue squares. Paint blue squares chromatically––a row of blue squares. And you go home and you do the assignment and you come back and they say, Tell me about your art. *laughter* RB: It’s not art; it’s an assignment: you told me to paint blue and I painted blue. Yes, but tell us about it. Describe it to us. I painted blue! I did the thing you told me to. *laughter* RB: So there’s an encouragement to lie and bullshit and make stuff up and make things larger than they are or need to be. And I’m not good at any of that, so. Yeah. So why did you persist for the year, then? RB: Well, I was already there. JLH: *laughs* *laughs* It would have been inconvenient to leave. RB: I had access to the cafeteria; I got my OSAP; my friends were there. So, you know. So you painted blue for a little while. RB: I painted blue until––yeah, I got too sick and left. And also a combination of being too sick to be in school and teachers being sick of me being in their school because I’m––because I was argumentative. I was a jerk. I was an asshole to the teachers. I mean, I remember hearing in an interview Noam Chomsky saying that basically graduate schools select for obedience. *laughter* I wonder, Luke, if that at all resembles your experience of––was it an MFA at Guelph? JLH: That I took? Yeah. JLH: No, sir. I have an MA in English Lit. And that was a little bit my experience. I resonate with Roxanna when she says that she was a jerk to her teachers. I was there also. And I had taken the thesis option to do my MA and eventually I decided that I was going to write––I was so frustrated with the whole thing––that I was going to write it as a personal essay, very much in a kind of visceral, personal way. And knowing the whole while that my particular supervisor would probably pass it, but that it would kill any opportunity to go do a PhD. RB: Look at you. JLH: Well, at that point I decided––I had always thought that I would do the PhD thing and go be a prof, but halfway through, I realized that I couldn’t do another five years. I didn’t think I could cope as a prof in the academic institution, and I had no idea what to do after that; I had literally no idea. And I’ve been bumbling along looking for a place to do stuff ever since. I have a very tolerant partner. RB: *laughs* So, on this point of the personal essay, written from the first-person perspective––something that is maybe suspicious in the lordly academy––I remember, Roxanna, a reading you gave that you preceded with an anecdote––that I hope you don’t mind my reiterating here––about your having taken a nightschool course with a serious heterosexual man-poet–– JLH: *laughs* ––Who encouraged his students to move from the first-person perspective to the third-, and that it was his opinion that shifting that perspective makes a more powerful poem. So, when you worked with Aileen Miles, her response was, Fuck that. Let yourself into the poem. Let everything in. If you’re sitting in a room writing a poem about your father’s death and a dog walks in, let that dog into the poem with you. And something she kept saying throughout the workshop was, I don’t see you in here--as though you were important enough to inhabit the poem. And that that was a strangely liberating idea for you. And you went on to say that it was really fascinating that the serious heterosexual man-poet advised objectivity and the serious queer poet advised subjectivity. RB: Wow. I used a lot of words all at one time like that? That does not sound like me at all. I must have written it down. It didn’t look at all like you were reading from a prompter. It seemed to be spontaneous, yeah. RB: Fascinating. So, Luke, as you mentioned, a personal essay wasn’t going to be the form that would allow you to proceed into a PhD––and Roxanna, as that move from third-person to first-person was strangely liberating for you––I wonder if either of you have any remarks about the importance of the first-person perspective, and whether that’s in contrast to what universities look for. RB: Hm. I don’t really know what universities look for, not having gone to one. I’ve taken a couple of night-classes, and I was shocked at how they encourage you to write terribly. JLH: *laughs* RB: Like, why do they make you use a lot of jargon and big words that don’t mean anything, and then they ask you to write your opinion as though it’s authoritative fact. And I just––that just seems gross and disguising your subjectivity as objectivity. Mm. RB: Those are two––objectivity and subjectivity are things I think about a lot in terms of––Those are things that have always concerned me since I was quite young. Things that are presented as fact that are not, in fact, fact. And we say they’re objective, but really they’re more like many people’s subjective opinion presented objectively. So, what does objectivity mean? And subjectivity is inescapable, but I have no clear answer. Now I’m rambling. It sounds like the objectivity you’re describing is basically subjective consensus. RB: Yeah. I like that. I might have to steal that. It’s yours. JLH: One of the things that I think is interesting when we get on that subject, is that I don’t think it’s impossible to write good poetry or good whatever from the third-person. But the risk that we run, when we speak in the third-person, is falling into the idea that we are an authority even when we’re not, or that we have factual basis for what we’re saying even when we don’t, or that we have an air-tight argument even when we don’t. That’s the risk of the third-person, when you’re dissociating yourself from your subject. So, you can do it, but that’s the risk. Just like the risk of writing from the first-person is that you rely so much on your experience that you don’t have any support for a larger position. And so, I think you need to know those risks when you’re writing in those modes. If I want to write in the first-person, I need to be able to understand the limitations of that; and when I write in the third-person, I need to understand the risks that that position draws me into. So, on this point of the third-person perspective, Roxanna, I was caught delightfully off-guard by your attack on authors’ bios and photos from 2014, which is framed as a guide and full of contradictions. After berating the conventions of the author-bio––the third-person perspective, how you generate income, publication history, academic affiliation, information about your pets––you go on to explain that author photos should be in black and white to convey the seriousness equal to the business of writing, and should also be full colour to convey that one is young and current and relatable. And one’s photo should ideally look nothing like you. The goal here, you write, is to be completely unrecognizable. RB: *laughs* I wonder if either of you have a response to the orthodox, writerly persona, and why it fails. JLH: Mm. RB: It fails? Do you think it fails? It seems quite successful. *laughs* RB: It’s slick, financially. It’s also––you know, no: I think it’s very successful. I think they’re doing okay. But it fails in a kind of heartstrings kind of way, right? I mean, introductions that are offered at readings often list the journals that someone’s been published in, or the awards that they’d been shortlisted for or won. And there’s something so anaemic about that. I think in that same piece you wrote something like, Why are these facts more important than one’s fucked-up childhood, or one’s weird secret habits? Why don’t we discuss those things? Those things seem to me to be more successful, in a way. RB: Well, they’re certainly more interesting. And make the person speaking a human being instead of a list of credits that are sometimes a little alienating, if you’re not familiar with the publications or if you’d never heard of them. Suddenly this person speaking is so much fancier than you, which makes you feel very intimidated. Or, that’s me. I’m projecting, of course. But, I don’t think I’ve ever gotten over the disappointment of learning what actual poetry readings and poets and poetry are like. JLH: *laughs* RB: Like, my childhood dream of––I remember being afraid, when I was twelve or thirteen, writing poetry and someone would be like, Oh, you’ll be a poet when you grow up. And I’m like, Oh my god. No. They go to institutions; they’re mad; they get locked up. I don’t want to be a poet. That’s terrible. They get locked in attics, or they die in gutters. I knew this already as a young child that that was a terrible fate, right? But exciting, right? And interesting. And then as a teenager, you want to be a poet because that’s sexy and they’re doing stuff and they’re hitchhiking and they’re having adventures. But then as a young adult, to realize, No, they go to school. JLH: *laughs* RB: They go to school and they have jobs and they’re just regular. And they all are still acting like it’s a job and it’s a regular thing, instead of this magical gift, right? Like from the gods or whatever. This mythical power to be a poet, and they’re just going to work, and they’re just kind of mean to each other––like it was just–– *laughter* RB: What’s the point? Why are they so mean to each other? We’re all doing the same thing. But no, you have to go to school. It’s so confusing! Everything I read––all the poetry I read as a child and as a young adult––it was so exciting and invigorating. And then to find out it’s not at all like that; it’s just another job; it’s like all the juice, all the magic got sucked out of it at some point. It’s continually disappointing that everyone is not just constantly: WE GET TO BE POETS! Like, this is an incredible––like, you are making art with language. What a gift! How lucky we are to be able to do any of that. But no, we’re just going to talk about our credits and our prizes and––I don’t know. I don’t understand it, and I think it broke my heart so much to realize that this was the case. You have to have a deg––Like, I remember the first time I heard someone went to school and got an MFA and it’s like, Yeah, but what do you mean you went to school to write a poem? Why? You already wanted to write poetry. What are they gonna teach you there? I don’t understand why––That seems the opposite of poetry. It’s just so confusing to me. All of it seems counterintuitive to poetry to me, which is the part that I rarely ever hear anyone speak about––the actual words, the actual lines, the actual poem. That’s what I care about. The rest of it is just––I don’t know––not even gravy. JLH: I remember that the first bio I wrote for a magazine included a whole list of things that I was into. It was a bio that said something about who I was, and I sent it to the magazine and they sent it right back, and they basically told me to give a list of places where I’d been placed. And yet, when you go to festivals and whatnot, the very first thing people ask is about those personal things. When they have a chance to talk to authors, what they want to know is, What went on in your life that brought you to this spot? They want to know about you as an author because that’s the point of human connection. RB: Mhmm. JLH: So it’s interesting that we don’t put that in bio’s at all, ever. I hadn’t really thought of that, but it’s a true fact. RB: I thought, when I worked as an editor, that putting credits in a bio was a short-cut for editors who are going through submissions: Oh yeah, this person has been in five different places; they’re probably good. That’s gonna make it closer to the top of my list. It makes it easier just to go through submissions, I think. Or, easier to sell the poet, or sell the work, because other people have already put time and money into it, so it’s worth it to take this person, I think. Subjective consensus. RB: And I think, Ew, gross. Just gross. JLH: And there’s a tendency to do that when you have a pile in front of you. RB: It’s easy. JLH: It’s easy. So, I might embarrass Roxanna here a little bit here, but that runs very counter to the way I encountered her work, for example. I’m in London; I’m tabling beside Baseline Press. I had never really encountered them before. Beautiful chapbooks. I picked one up; it was Sam Cheuk. I read it; I was really impressed. He’s supposed to read at Knife|Fork|Book, so I go to Toronto to see him there. He doesn’t show up because of something––I’m not sure what––and I’m talking to Kirby, and Kirby says, Well, we have his book. And I’m like, I already have his book. What can I spend my money on? He says, You gotta read Roxanna’s book. And I read it, and I’m blown away by it. And so I decided to review it. And those kinds of organic ways of running into people and discovering their work and being influenced by it, and having it take you to somebody else, who takes you to somebody else––it feels better to run into people that way. And it’s harder when you’re faced with a pile of submissions: you don’t know anything about those people, and you’re just trying to read one manuscript after another. Yeah. You’d much rather do it the organic way. RB: It’s slower to do it organically, too, right? JLH: Mhmm. RB: The same is true for me when I’m to work with a publisher. The manuscript unmeaningable had been accepted by a couple different publishers whom I turned down--which was a weird thing to do--because it didn’t feel right. But this did, working with you, Luke, and working with Shane. I knew I wanted to work with someone who liked what I was doing, but would also understand me, and that I’m not on social media, and I probably say inappropriate stuff sometimes, and I rarely leave my house, and I’m weird. I like having a publisher who just let me be myself without making myself ill to promote the book. Like, you’ve been so flexible with me and made sure that the launch is held someplace accessible and taking those things into account, which a lot of publishers don’t do at all. The publishers that I decided not to work with, it was for reasons like that. Publishers who had their offices up a few flights of stairs where I would never be able to go. Those kinds of things. Luke, you’re talking about that sort of organic and slow process of discovering new writers, at least in that instance, being facilitated by Kirby, and I just wanted to tip my hat to that entity of Kirby. JLH: Yeah, and the brand new space. RB: Oh, absolutely. JLH: We’re gonna be launching there on November the 27th at the new Knife|Fork|Book space, which we’re really excited about, and Danny Jacobs will be in town from out east at that point. He’s doing a unique thing there, Kirby. There are not a lot of places in the world where you kinda get that vibe of somebody who just really loves what they’re doing, and who’s taking some risk and doing some fun things. He’s been in business for like three years and he’s already launched a second imprint geared specifically towards queer poets. And he’s just doing really good work. I tip my hat to him for sure. RB: Kirby’s an angel. Kirby’s like the fairy godparent of poetry. Angel, angel. Love, love Kirby. And the love for poetry–– JLH: Yeah. RB: ––is incredible. That’s just pure love. KFB is just fueled by poetry and love. Yeah, the way that that organic facilitation of community takes place is because Kirby reads every book on the shelf and every book coming through–– RB: Mhmm. ––And it’s totally out of a place of love, yeah. RB: Mhmm. So, Roxanna, speaking of working with Shane: after a cursory study in anticipation of this interview, it seems that people with disabilities have historically been almost anthropologically studied and spoken for by people without disabilities. And I wonder, in contradistinction to that––sorry, this is an unnecessarily large word––opposing that, you’ve had the opportunity to work with Shane Neilson as your editor, and I wonder if you’d talk a little bit about that experience and what that has meant for you. RB: Oh, everything. Everything. No one else could have edited that. Shane has spoiled me for all other editors ever. JLH: *laughs* RB: One day there will be a statue to Shane, you know? I look forward to the day when Shane wins The Order of Canada for all the work he does. Fuck yeah. RB: He’s a powerhouse, and such an incredible poet, and he was so good with me. I remember the first email he sent me had lots of words I didn’t understand. And I thought, Oh, no. He thinks I’m a went-to-school smart person. *laughter* RB: And I had to email him back and say, Could you please dumb everything down and explain it all like I’m five, please? And he did, in a totally not-condescending way. He took the time to really patiently break down words I was not familiar with and concepts I didn’t understand. Which meant a lot. Not many people would take that time to do that. And Shane being disabled and working so much––his activism work for disability, and he’s doing a thesis, I believe, on pain. I think he defended it not long ago. RB: Did he? Yay, Shane. JLH: Yep. RB: Good lord. Does he ever sleep? JLH: No, he doesn’t. RB: *laughs* Good grief. But I could not have––Nobody else could have edited that, I think. They couldn’t have understood it on the multiple levels that Shane did. Not just the subject matter, but also, you know, he’s a fantastic poet himself and he’s a driving editor. Anything wrong with the book is my fault totally ‘cause I’m stubborn. I can’t think of anyone else who could have directed it and guided me and given me editorial feedback in a sensitive way, cognizant of where I’m coming from and altering the way he communicates so that things are clear for me. It’s a big deal. It takes time to do that. It’s extra effort for him to explain things to me that he might not have to with other people who are more educated or who are better at words––at like, speaking or communicating. So, I really appreciate the extra effort that takes and that he gave and didn’t complain or make me feel small or diminished for needing that support. Let me just––before I ask Luke to discuss the evolution of his relationship with Shane towards co-founding Gordon Hill Press––I just wanted to say that after having produced a book like unmeaningable and the fluency and honesty with which you’ve spoken so far, I’ve got to challenge your––You just seem to me to be an expert communicator, and the poems are astonishingly fluent, so. RB: Thank you. Thanks. Luke--so, how did you meet Shane and how did the conversations preceding Gordon Hill Press look? JLH: We met in the unlikeliest of places for poets, maybe, these days. We met in a church hallway. *giggling* JLH: And he was introduced to me by the pastor who said to the two of us, Oh, you guys should know each other. You’re both writers. And I thought, Well, that could mean a lot of things. And we shook hands and looked at each other awkwardly and we went our ways. It was funny because I had read some of Shane’s work earlier, but I had never seen a picture; so I didn’t know who I was talking to. And it sort of dissipated. And then we ran into each other again a little while later: I had written a review, and his first words to me were, Why did you like that book so much? There was hardly a hello. And we had a twenty-minute conversation about this review, and then I started to realize who he was. And we had a few conversations over time. Got to know each other a little bit. We have kids aged similarly. And then one day he showed up on my porch out of nowhere and he came in for a coffee and he said, We should buy Porcupine’s Quill. Wow. JLH: And I said, No one will ever submit to me. He said, That’s okay. They’ll submit to me. And we had that chat. But that was a really long kind of process before we realized that buying PQL wasn’t going to happen. But by then, we had all of this work done. And by that point we said, Okay, let’s just start something on our own. And it’s probably worked out better in that we were able to do some of the things that were important to Shane, which is to have a real emphasis on representing people with disability, people who haven’t been––not unrepresented, always, but not well represented. And we wanted to have a real emphasis on making sure that people were able to do what they were able to do. Right. JLH: So we had that element to it. And also, it meant that we were able to make it very representative of Guelph. Guelph has never had a publisher of any kind; and it’s weird, because we have a university there. But, because it began as an agricultural college rather than a religious college, it never saw the need to have an academic publisher. And that lack has spawned some interesting micro-publishing stuff there, but we thought that it was a good idea to have a connection between the local area and the larger nation and the larger work of literature. And I want in particular to have that element. So it did give us some unique opportunities to kind of pursue the things that we’re passionate about. But we hadn’t planned it as such. It kind of spiraled out of control from a meeting on a porch. So, to take a look at unmeaningable, Roxanna, I notice a compendium of texts that informed the work, and that there were a number of sort of inverted recurrences of lines from T.S. Eliot, the first being in the second line of the title poem “The Trick”: |