Interview with Vicki Miles

Interview conducted by Kevin Heslop

|

|

This conversation took place over the phone on October 17, 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Ms. Miles, let’s begin with a stanza from Hass:

The old art historian. I was going on

About Cézanne and he took me into the studio And stood me in front of an easel with a brush And said, “Now, put these on paper In small rectangular daubs so that they shimmer, And until you can do that, I say this In all friendship, shut up about Cézanne. *laughs*

In other words, unable to put small shimmering daubs on canvas, I admit at the outset that I won’t shut up about Cézanne, so to speak. But, I notice—I’m looking at a painting of yours of a self-conscious young woman and two young strutting men in bathing suits near an apparently cellphone-preoccupied youth on the pier with a lighthouse in the distance. And I wonder whether we could begin by talking about rendering people as they are rather than as they might be. Does that resonate at all? Yes, I do gravitate towards the more real rather than idealized, or—I would say I’ve somewhat romanticized, stylistically: the colours are a little brighter, the lines softer. I can’t seem to help myself doing that. But I start with what I see through the viewfinder of my trusty Nikon camera and I knew I had something one day when I was at Grand Bend: I was just wandering along the shore looking for photographic subjects, and I saw these young people—I saw two versions, one just with a boy and a girl, one with three boys and a girl. Did I send you the one with three boys and a girl? Yes. Okay. So, they wandered out to the end of the pier together, obviously a ‘together-group,’ and then—just, I caught it. I caught it—that moment when—the one guy looking cool in his sunglasses; they’re tugging on their bathing suits—they are so self-absorbed, so aware of their own bodies that it negates everything else around them: they might as well have been alone. And it’s that particular age, that teenage moment, that constant, almost painful over-awareness of your own body, your own facial expressions. It’s a self-absorption that you don’t see later on in people in their twenties and thirties when they get comfortable in their own skin. I knew I had to catch it with my camera and then paint it because it just spoke volumes. They’re just together but alone. So yeah, that’s what I saw in that particular moment. So how, as a highschool visual arts teacher, does one go about approaching—about the process of teaching a herd, together and alone? And what did teaching teach you in this regard? You teach to the individual. You have to acknowledge that awareness but also their insurance: their body is never right; they’re never happy with it; they’re not happy with the shoes they picked that morning. And I have the luxury of, instead of standing and teaching one math equation to every single one of those thirty students, they demanded my individual attention. You guys weren't all doing an identical painting or drawing; and that allowed me to move from person to person. And, if it was an overloaded classroom, maybe I could only give you 30 seconds, but you had me fully and completely for that 30 seconds. I was completely into you, if that makes any sense. It does, yeah. And it reminds me of the responsibility of the editor not to impose their vision but rather to kind of temporarily live in another person's vision and then suggest ways in which to improve or enhance it. Was there ever reluctance about offering those kinds of suggestions? I like to think I read people quite well. If I knew it was a student who was on the edge of tears, maybe something bad happened at home that morning, or if they just looked distraught—or, not even that, because sometimes it was so subtle—it was just that they were fragile, for some reason. And then, the only thing I could say, even if I could say something constructive, like “You should really use cerulean blue instead of aquamarine,” The only thing I could say in that moment was You're doing such a great job; you've really mastered watercolour; or, you’ve come a long way. Because that's what that child needed in that moment. I didn’t have my teaching hat on all the time. And, you know, the constant You use the paint this way; you try this different color combination; remember your colour theory! At a certain point, that curriculum-based stuff goes out the window, because there's something more important, there’s a person there, that needs me, and not my drivel, if that makes sense. It does, and I feel like there's a distinction between that hyper-self-aware, hyper-self-conscious sort of window of time that we all pass through in our adolescence that seems to me to be the opposite of the way in which, in John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany, Owen Meany believes— Oh! Did you read that? I recommended that, didn’t I? You did, yeah. I didn't get a chance to read it but I did read a couple reviews of it and a summary—I admit the summary was through Wikipedia. *laughs* But Owen Meany, um, in contradistinction to those hyper self-conscious adolescents feels himself to be a self-oblivious instrument of God. And I'm thinking now also of Michelangelo's line “My Lord, free me from myself so I can please you.” And I'm wondering whether that sense of being acted through, as an instrument, freeing oneself from self-consciousness in order to do one's work, resonates at all with your practice as an artist? Um, well, you just said a mouthful. Do I believe that God imbues me with the ability to paint just like Michelangelo did? *laughs* I mean, he really did believe that he was an instrument of God and that he was literally a God-given talent. And that that was—I don't believe that, I believe I am a mediocre artist. At best. But I'm grateful for what I am able to do. I recognize brilliance; I'm not there. Does it bother me? Nope. And I don’t know how much God has to do with it. I am spiritual, but I'm not religious. So, there you go. On that note, I have a few simple questions to get us going. What is nature, Ms. Miles? What are we in relation to nature? And also, what does an artist do?

An artist can only make a poor replication of nature; we’ll never do it justice. Whenever a kid would say, Ms. Miles! Ms. Miles! I'm going to paint a sunset! I—I haven’t painted sunset because you have to be there. And being on the beach, I've seen spectacular sunsets, and you can't paint them and do them justice. So, when we do the more manageable things, like a pass through Springbank Park or whatever, we're paying homage to it, but we'll never ever rise to the occasion. There's no substitute for walking along that path, for hearing songbirds; it’s a multi-faceted experience that can't be captured on a two-dimensional canvas. As far as nature, philosophically, I adore it; I love it. Yes, we're making a mess of things: we’re just doing horrible things to precious lands, precious waters. And I feel, as part of my generation, the baby boom generation, born just after the Second World War, that we didn't do enough to halt this, that we're leaving a legacy for my granddaughter’s generation. They’re going have to clean up our mess. And for that, I feel ashamed. For all of us.

Well, I’m reminded of a recent discussion hosted by the Fiddlehead of a poet talking about how she began to see garbage—single-use plastics, cans, cups and so forth—as the remnants of people's joy rather than evidence of individual irresponsibility. Corporations are responsible for the production of these single-use plastics and garbage, she observed, pointing to Pepsi’s commercial “litterbug” campaign in the mid-twentieth-century—not the individual people who’d simply put garbage in a bin, which would be transported to the foot of a mountain of garbage, which would itself be shipped elsewhere, which even this fair country of ours has been responsible for, lately. But anyway—which is to say that it’s a systemic rather than a generational concern, I think—but anyway do you—what is the place of art in response to systems-collapse—to economic and environmental and habitat collapse? Is there something that the arts are specifically well-positioned to catalyze—that other domains of experience can’t touch? As far as visual art, I am fascinated by those forward-thinking artists who are actually making art out of refuse. Some of it is brilliant. I think as artists, the more powerful avenue is through music; I see that as a more powerful venue. I mean, people respond to it. And it's more widely available. You know what I mean? Painting’s still considered elitist and only within a fairly select group who are interested; music is a more universal art. And it seems to me that everything from rappers to Cardi—Aren’t you impressed with me? Yes. Well done, Ms. Miles. All the other, you know, the ones who are currently on top of the charts, they have the power to do something as artists, far more than a visual artist. I think poetry and painting are probably siblings in that sense: they’re often thought of as sort of elitist vocations that require an education whereas music’s ubiquitous. I also notice that you're going to scoring points by mentioning Cardi B and I'm going to be scoring points by mentioning, like, Mary Pratt and Caravaggio. Okay, we can trade those points back and forth. I'm not sure those points are of equal value. But I'm looking at a painting of yours which features a child crouching in water, in a lake, presumably, which feels reminiscent of Mary Pratt in its ambition to capture diffractive light on startled water. And it's just an astonishing piece to kind of contemplate. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about that painting in particular perhaps in contrast to the sort of adolescents in the earlier image that we were discussing? That is one of the few paintings I've done that is not from my original photograph: it’s one that my niece took of her little boy, Luke; and that's actually on the Pacific Ocean. In part it was a technical exercise because I've been determined to conquer water, in oil, acrylic, and watercolour. Did you know that—I’ve probably said this—the two hardest things to paint are water and fire? So that was partly a technical exercise. But, also, he’s a lovely child, my grandnephew, and just at the age of about one and a half. That age fascinates me because the learning curve will never be so rapid and ascendant. And also, the handling at that time by parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles can skew that so badly—or to such a good place. You know what I mean? Yeah. It’s such a delicate age and needs to be handled right. So, he fascinated me—besides the fact that I'm related to him. The picture caught me because, I mean, there he is sitting at the edge of the Pacific Ocean. And what's in his little head? *laughs* The vastness of it must be absolutely overwhelming—or is it? Maybe he thinks, Hm, cool: ripples in the water. His little brain is just forming and reacting and growing so much at that age. So, it was just partly driven by that, and partly because I had painted several scenes of Lake Huron water, which is mostly mossy brown. And, so, the chance to paint more pristine waters that have that cerulean blue in it got me going too. Just as you mentioned cerulean blue I realized that I'm speaking with someone whose experience of colour’s spectrum is vastly better-tuned than mine. And I wonder—In a previous conversation, you mentioned that you've been drawing for about as long as you could hold a pencil, and I wonder whether, over the course of your development as an artist, whether you felt like maybe you began in a place of synesthesia? Were you were automatically associating emotions with colours, textures, images, forms, structures, or has that ability deepened with time? What has colour allowed you to think through? What associations do you have with colors? Do you associate emotions or moods with colors? And to what extent is that intuitive as opposed to cultivated or socialized, for you? When I started drawing and painting, it was purely a technical exercise. I was experimenting with how it reacts to the paper––using linseed oil versus walnut oil, say—and it was all a technical exercise. Maybe I've been over-educated. I’ve been asked, you know: Why did you paint the walls of prison cells pale pink? Because it's proven to be calming. *laughs* And I think, at some point in my art history lessons—that would have been grade twelve—I said, when I was talking about Paul Klee, I hope I have not over-educated you. Sometimes I feel over-educated because I just have so much art history in my head, so much colour theory, that it kind of sucks the life and the emotion right out of it. And I worry sometimes that I almost approach it too technically. Although it does get me in the gut—like that picture of the kids on the pier in Grand Bend. That got me because I thought that encapsulated every teenager I've ever taught who was on that precipice so vulnerably. I mean, that girl’s in a bikini; the boys, you can see their bare chests. So that one knocked me in the gut. Sometimes my paintings are more of technical exercise with water; other times, it just gets me. Education is great but it also—I mean, I'm sure that in writing classes you thought, Oh my God: I've dissected this ad nauseum and now I don't feel anything for this piece of writing. And I say, I find high school English classes are very guilty of that. You guys were forced to dissect what, Death of a Salesman?

Romeo & Juliet, say—in grade nine. And you wanted to just throw up and never see the book again—and that’s wrong. I was recently encouraged by a nameless writing studies professor to mention in my new book that I failed grade 11 English twice. Well, I hope you feel good about colour. I just met a former student in Port Franks. She came up—Ms. Miles!—she was on a golf cart with her kid. And after a fairly lengthy discussion, she said she enjoyed my class; and I said, You know what, I never expected any of you to go out and be the next great Picasso. But if you decided, calmly, that you wanted to paint a wall in your first apartment red then goddammit I've done my job. *laughs* That confidence in colour, colour that makes you feel good. If that's all I accomplished, I'm happy. So, I suppose that there's a difference between the mediums here—between the paints and what one might be bludgeoned over the uncomprehending head with in an English class—because the language of experience and color and texture and shape and rhythm are all intuitive languages to us, whereas ostensibly Modern English is not. Mom and Pop, Billy and Belle don’t spout iambic pentameter, so to speak. First of all, words alone on a page terrify some people. Some people are dyslexic; some people have been bludgeoned with literature from early ages: You must read this because this is in the curriculum. Whereas with art—and again, it's like that elitist viewer—museums and art galleries scare people. Like, the gallery where I had my stuff in Grand Bend last year—I would hang out signs saying Come on! I had to encourage people to step in the door, and say, This isn’t scary. And I would explain paintings to them (if they wanted an explanation) or just let them see. And I think, when teaching art, every kid's opinion is valid. The first time I introduced abstraction—Of course, in grade nine you will always have a kid who says “My little sister could do that in kindergarten.” Well, yeah, but let me delve further into that for you. And then to point out that they're right, I would show them a painting I got from Ms Haggerty: I said, What do you think of this one? Some said, I like it; some said, I don’t. Well, this one was painted by an elephant at the Edmonton Zoo. So, you're all right. And that was what I like to consider one of my “aha” moments with grade nines—to say, yeah, you didn't like the painting by Pollock, who splashed paint all over, but you liked the elephant one. Guess what? You’re right. And it's easier to do that than to say, Romeo and Juliet is a great piece of writing. Because, you know, the kids says, Prove it. *laughs* *laughs* I’d have a hard time proving it. So yeah, visual art is easier, in that sense. It felt like the literary equivalent of tearing the petals off and crushing them and running the goo through a spectrometer in order to determine why a rose smells so pretty. Mhmm. There was a way that you have to destroy the thing in order to analyze it, to dissect magic. And I wonder whether you ever had that experience? Does your knowledge or fluency in art history ever detract from your experience of the paintings—or only enhance it? Enhanced it, largely. I understand—I reserve the right to like some paintings and not like some paintings just like that little grade nine students—we all have that right—but I was afraid I taught the joy out of myself in reacting to paintings. And then, once I was at the Albright Knox Gallery in Buffalo. I walked into a room; and the only thing in that room was a huge Jackson Pollock painting. And it was so big that it took up the center of your eyesight as well as your periphery. And then I just realized that my face was wet. Wow. I was just crying. Tears were streaming down my face. I was so grateful in that moment that I had such a powerful emotional reaction. It was the most beautiful thing I'd ever seen in my life. It was glorious. And, of course, I knew about Jackson Pollock—I taught him—but I was so happy for myself that I was able to have that gut reaction and to respond with tears. And yet, I've been to the Vatican: and even though Michelangelo’s sculptures are unsurpassed—and I was born and raised Catholic—I was in front of his Pietà and I didn't have that emotional reaction. I had tremendous admiration for the smoothness of the marble but I was more taken with trying to find where some crazy guy came in a couple decades ago with a hammer and smashed her hand off; I was looking for the breaks in her hand. *laughs* *laughs* And yet, why did I start crying when I saw the Jackson Pollock? It’s just that that's the way it should be. … Do you you know what I mean? Yes. And what did Jackson Pollock teach you? That if you do it right, painting is pure joy. He was driven; and I think I teach—did I teach you grade twelve art history? You did. Okay. So, Michelangelo believed that the power came straight from heaven and through his arm through to the chisel; and he much preferred sculpture over painting. (He hated painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.) Jackson Pollock believed that the power emanated down his arms directly from God into those giant cans of latex paint that he punched holes in the bottom of with a screwdriver and started swinging around on the canvas. That tremendous ego was fascinating to me. I don't have an artist ego at all; I just like to paint. But that—that God-like sense fascinated me. And I'm beyond understanding it: I don't get it. But, I also, that applies to the idea that you have to be (a) crazy; (b) alcoholic; or (c) heavily into drugs to be a really good artist. Pollock was a raging, raging alcoholic. And he was—you told me you saw the movie? Yeah. Yeah, it was Ed Harris-- Ed Harris. Ed Harris spent ten years bringing that to the screen because he wanted to do it right. And from all my readings about Pollock, he did. Pollock was a tortured soul. Do you have to be a tortured soul to be an artist? No, I don't think so, but it sure seems to help. Yeah. *laughs* Self-torture. I would have loved to have met the man. And you know, God bless the woman who stuck with them for all that time and whose own art was brilliant and she, second banana. I mean, she stepped aside so that he could achieve brilliance. But—and people look at the pictures, but—no, that man had an innate sense of his pattern and texture and overlaying of different subtle colors. I like the ones that are just kind of browns and beiges and blacks; I think the ones of bright reds and yellows and blues—but every moment he was contemplating whether he needed to whip the brush at the canvas or if he needed to push the hole in the bottom of the can like he knew what he was doing. And he was doing that at a time when—Lord knows—no gallery's ever gonna look at him twice. Until, well, Peggy Guggenheim brough him on board and a star was born. Well, here's me returning a contemporary reference to the phrase A Star Is Born, this adapted film interrogating celebrity, which, um, is something that Pollock, after he was elected by Guggenheim to the upper echelons of the modern art world, suffered from as well, mingling with alcoholism. I also wanted to mention his partner's name: Lee Krasner. But what do you think that fame did to him? What does fame do to artists? Why is it that fame is often incompatible with art? It doesn't always happen that way. That’s just—look at Justin Bieber claiming that he's been all messed up because he achieved fame so early; Pollock didn't handle it well; and yet, Claude Monet, once his paintings—you know, his paintings were beautiful, but I mean—then he built this studio and he built his sales room and he just made it into a thriving business. He was one of those artists who in his lifetime was making money hand over fist from his work. He was happy: you see him sitting in a chair smoking his pipe and painting en plein air and he just, you know—so they're not all tortured souls. He was a good businessman and fame didn’t phase him, He used it; he knew how to use it. Mary Pratt did, too—so did Christopher Pratt, her husband. It seemed to be that rare combination of good artist and savvy businessman. Salvador Dali was another one: he took advantage. His technical skills are beyond the pale but man that guy could not only sell his work but sell himself.

That's the thing. I don't know if Dali believed that his paintings came from god to him; it may have been the other way around. *laughs* *laughs* Yeah, God was second fiddle to him—although interestingly he switched to Catholicism later in life. After he met the Pope, actually. Hm. Interesting. That is interesting. But probably not relevant. Neither of us accord particularly to the idea of linear time, so everything’s relevant in the spiral time of the moment. *laughs* *laughs* That’s true. Or everything is irrelevant, depending on one's perspective. Yes, true. I'm happy to join you in relevance or irrelevance, whatever it is that we're we find ourselves in at the moment. But: Vivian Maier. Um-- Did you get a chance to look at some of her work? Yeah, and I wonder if you'd say a few words about what in her work—which, sort of through the gruff of the city rather than the shores of Lake Huron—seems to me to share with your work a gift for capturing moments framed organically rather than elevated. I have that woman on a pedestal. And it's ironic that now everyone thinks that because they have a camera in their phone they’re a photographer. No, it's a rare, rare talent. And her capturing the grittiness of the street—She was in Chicago, wasn’t she? Yeah. Chicago and New York. New York and Europe and back to New York, I think. Yeah. And just the beauty that she found and all the grittiness; and sometimes they're so ugly they're beautiful. Yeah. And some of them made me cringe; and just to, again, in photography—we are so inundated with images—she touches something--every single photo she takes. She's absolutely brilliant. And sometimes I take a photo—these don’t sell, though—I, one thing I like of mine, it’s a blue box at the side of an old house. *laughs* Nobody’s gonna buy a picture of my blue box. *laughs* But it was the perfect composition. But, again, you have to paint what you know and what you like, right? If you start pandering to the public—although I have shamelessly done that: I've done a couple of beach scenes; they flew out the door—though it was partly self-satisfying, just trying to conquer water. Vivian: the streets didn't scare her; her subjects didn’t scare her; she knew which ones were worthy of capturing at a time when film was really expensive. And film developing was really expensive. Which, I guess, is why that guy who bought the [lapsed] storage-locker had—not hundreds--thousands of undeveloped rolls of film. Yeah. Because she probably couldn't afford it. Yeah. But each one of those little canisters of film has twenty-four pictures of such brilliance. You didn't waste film then: she had to know, at that moment, this is it; this is the one. And you know, I have the luxury of acryllic and oil: you let it dry for a day and then you paint over it, right? With film, you’ got one kick at the can—that’s it. So, I hope you enjoy looking at her work as much as I do because man she's right up there—right up there with Pollock and Michelangelo. Good company. I'm looking at a watercolor of yours, at the moment, of sunflowers, this field of sunflowers … That painting touched me as well. That field is called Max's Minions.

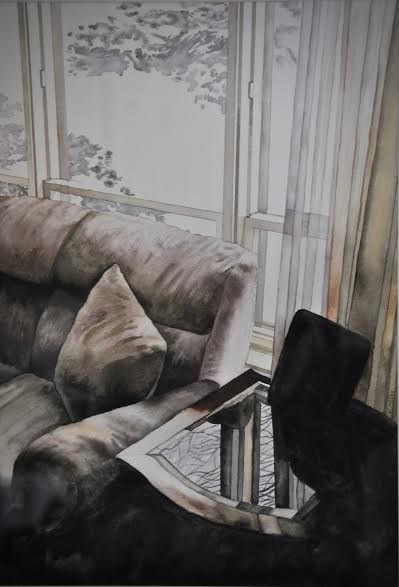

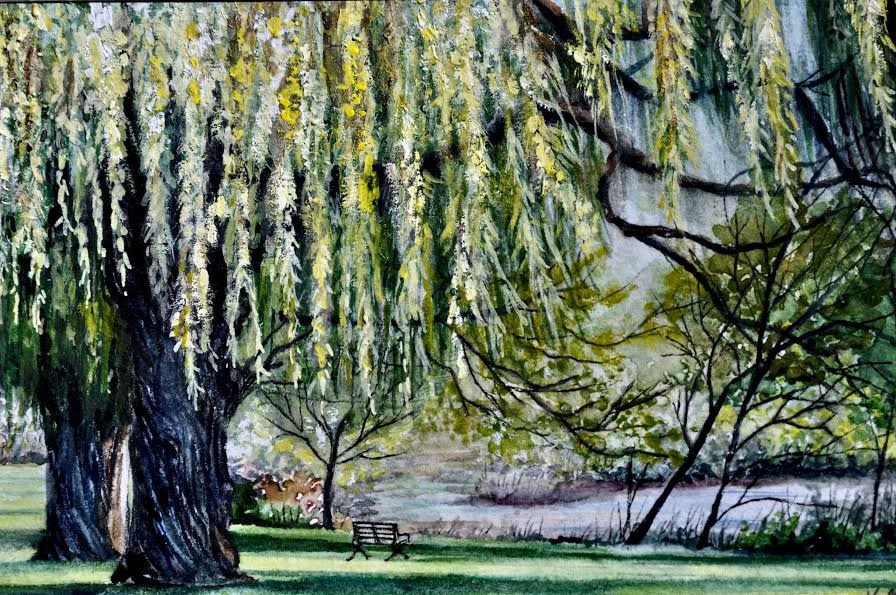

Right, I read about this. You did? Yeah. I’ll include a link to the article in the transcript. So, Max was a little boy who had leukemia—and lost his battle with leukemia—in Forest. And it just … People can be so good. Mm. Farmland is valuable, right? It’s your living; you need to grow plants; cash crops of soybeans and corn and wheat that put food on the table for your family. This guy took five acres of his farmland and planted it all with sunflowers. And the goodness of people: there’s just a wooden cashbox on a post and for the pleasure of wading into the field of sunflowers and taking a million selfies-- *laughs* I must assure you by the way that I've never—Well, I’ve taken one selfie of myself: spectacularly unsuccessful. Be that as it may, people donate money: they’ve raised thousands of dollars for the study of childhood cancer. And then guess what? Other farmers along Highway 21—which goes up from Forest, Port Franks, Grand Bend, all the way up to Bayfield, all the way up to Goderich—other farmers start planting fields of sunflowers for the same thing. Just a very trusting cash box for you to put your money into so you can take a picture of yourself with some sunflowers. Genius. And so trusting—and from such a good place in the heart. So, so Max lives on. So yeah, that painting is—it was a bitch to paint all those sunflowers. *laughs* But I did it with joy in my heart because Max, this is for you. And now I'm looking at a painting of yours which features willows and a bench by a river. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about that and what it represents for you. That was in Gibbon’s Park. And just—those willows have to be, have to be, over a hundred years old. And just for something to live that long, just growing green leaves in the spring and quietly going to sleep in the fall, and just how tiny that park bench is: the whole idea of nature dwarfing man is what struck me. You know, we make this little tiny park bench so we can sit beside the river and enjoy nature. I didn't want the tree to appear menacing, but man, they’re dominant. Hmm. A good thing for us to remember. There's another image: a wall with creeping vines across it, a kind of garden in front, and a boxed garden extending from the wall. And a gas meter. I called that “One Meter” because I could. That’s one of the paintings I’m—You don't always like your own work. I really like that painting. Me too. I was just walking up Talbot Street with my camera looking for something that struck me as more than suitable to paint. That house is at the corner of Talbot and Mill Street and—it’s not one of the grand heritage homes that has a pretty blue plaque on it—it was just kind of beat up. But that gas meter is beautiful. And for me, it was about my favorite time of day to take outdoor pictures: four o'clock in the afternoon when the light is really warm and it's getting low and it casts some pretty dramatic shadows, the shadows of the vine. And it was winter so there's snow on the ground and everything is dead but it was so alive: the image was alive. You know, the ivy was dormant and I think there was some eucalyptus in that wooden boxed-in garden that was valiantly trying to keep its head up through the snow but I loved the image. I knew I had to—It’s one of the few I painted big: it’s a very large watercolor. And of course, it hasn't sold. *laughs* I might not sell it. I don't usually form emotional attachments for my own paintings but I like that one. And it's also beauty in the common. Who would have thought: a gas meter? But I like that one. It may have been a generational cynicism that reaches its zenith on Twitter but I was thinking that this was a—Look at the way in which indomitable nature is being like sort of skewered by the compulsion towards an industrialized blah, blah, blah. You know what I mean? I think I might have overlooked the beauty in it by trying to perceive some kind of political statement or ecological statement that wasn't necessarily there.

To me it looked like everything was all sympatico; it was like everything was happy: the vines were happy climbing on the meter; the meter was happy standing there. No harm, no foul. They were working together. But I have to ask you a question: What does cynicism mean? I think it has something to do with, um, the presumption that everyone's self-interested, motivated only to achieve ends that will serve themselves and maybe their immediate families; and their desire, ultimately, to kind of maximally reproduce for their own benefit and to be, um, incapable of sunflowers. Hm. Okay. But they are, as we know. I do. It feels like my generation is extremely disillusioned with the people who refer to themselves as our leaders because we recognize that those people don't actually have the interests of the populace in mind or at heart: the majority of the population is functionally, procedurally marginalized to serve corporate interests. And that creates a profound distrust of the people shepherding us into the dark. That makes everything feel dark. I mean, there is a reason why the guillotine came about with such precision at a certain point in history. *laughs* I think that the King’s head need to roll. It comes down to the old, you know—money drives everything. Money is the power. Money is power. Well, I wonder if we could look at another painting by which to approach denouement. Oh, you want me to pick a painting…? Do you have them in front of you? If not, I can identify another one. I don't have them in front—You were going to narrow them down and make seven to ten that you thought you would best be able to write about, or that touched you in some way, or that you felt an urgent need to write. On a huge forked piece of driftwood running out of frame sits a young woman in a bathing suit above waves that are rolling in and she’s—She looks 10 to 12 feet above the surface of the water—And we get a long shot of the of the water and the horizon at about two thirds, or a little more than two thirds, of the canvas. Do you know the one that I'm speaking of? No. She looks like she might just contemplate the possibility of jumping. But she's also obviously slid herself along one of the two forked branches which-- Oh! That's actually on the Port Franks beach. And part of the fascination with that is that there is a tree embedded in the sand about twenty, thirty feet into the water. It’s been there since the year 2000. And it started out—That’s why you need to come up, you need to see that tree—It started out—Lake levels are at an all-time high right now and in the year 2000 lake levels were very low. So—and I’ve asked people who’ve lived here for twenty, thirty years—and it seems to have gotten dropped by a storm. This is as close as I come to believing in God: God, did you drop that tree on the Port Franks beach? And now, with high water levels, it's been the favorite place for kids to play on, to jump on. When the beach is emptier, the seagulls take over. And when I was watching—Again, walking down the beach with a camera because you never know when a paintings going to jump out at you—She was about nine years old and she’s sitting on the branch. And actually, if she jumped, she would jump into water that’s about ankle-deep. There's nothing dark about this because at the Port Franks beach the water is really, really shallow for hundreds of feet before there's any kind of drop off. And now you can psychoanalyze me because she was actually sitting with an older man I assumed to be her father next to her and I cut him out of the picture; I just wanted her. The age struck me. And maybe this is all my experience with kids. Nine years old is a really hard age. I don't know if you can remember when you were nine: you’re no longer a child and cute and you get your cheeks pinched and hear aren’t you sweet but: your body is awkward because your legs are too long; your torso’s too short; your face looks funny because you haven't grown into yourself yet. And, so. she is what fascinated me. And she was the subject. So, so, sorry Dad, you got painted out of the picture. But the way I painted it it was just a girl. Same with when I was looking at that little one-and-a-half-year-old boy asking what are they thinking? Maybe they’re not thinking anything at all. Maybe I'm superimposing my own thoughts on them.

Doesn't art solicit that kind of projection? Sorry, what’d you say? Doesn't art ask for that kind of projection—of the viewer’s own internal psychoanalyzable shit? Right. And that's the way it's supposed to be. Somebody looking at that could say, Oh, that girl looks so sad and lonely. Somebody else could look at it and say, Oh, she looks like she's having fun on the branch. And it's all valid. Whether you like the painting done by the elephant or not doesn't matter: if you like it, it’s absolutely right and valid. |