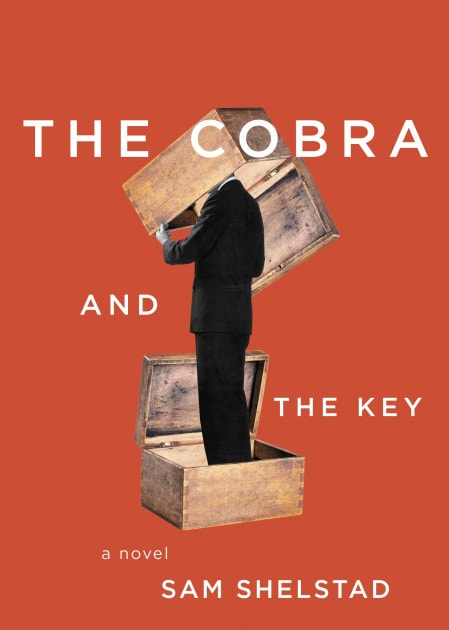

Henry Adam Svec Interviews Sam ShelstadSam Shelstad is the author of the novels The Cobra and the Key and Citizens of Light, as well as the story collection Cop House. He lives in Toronto.

Henry Adam Svec: Sam, your new novel is in the form of a writer’s manual or guide for the aspiring novelist. I’m curious about your own relationship to these kinds of books. Did you read some of these when you were getting started as a writer? Did you need to read or reread a bunch while writing The Cobra and the Key?

Sam Shelstad: I took an introductory Creative Writing course in university, long before I started actually writing fiction, and the professor assigned a very basic and practical guide. He admitted that the guide was a bit corny and to take the advice with a grain of salt, but that there were helpful things in there. When I started writing stories I read through the guide again and absorbed all the corny advice. I think that kind of thing is really helpful when you’re starting. To have really simple, practical advice on hand to hold your hand a little. It was this kind of guide that I wanted my novel to look like in terms of content: go through chapters on plot and character, etc., covering the cliche sort of advice you see over and over again. Use these as jumping-off points for jokes and to forward the plot. The other two books that really informed the novel were Stephen King’s On Writing and James Wood’s How Fiction Works. Have you read these? They're both great. King’s book is a guide that contains a lot of autobiographical material and the author uses his own work to illustrate his ideas, which is something I also needed to do if I wanted to turn my guide into a novel. And I thought it would be funny that Stephen King has license to use his own material because of his insane popularity, but my protagonist hasn’t even published a book yet. Wood’s book was influential in terms of style and how the book is laid out. Short chapters that focus on one idea at a time, simple chapter headings, and even the book’s smaller size. He starts his book with this metaphor about “the house of fiction,” which gave me the idea to start mine with the convoluted “cobra and the key” metaphor. HAS: I wish I had read some of these guides when I was younger, as I think they might have helped. I found it difficult to move from songwriting to longer-form fiction. I’ve more recently read the Stephen King book and some screenwriting intros. I think I underestimated how useful “rules” of any kind could be. But many of these books are written by people who have been working and reading and writing for their whole lives, so you can get a whole aesthetic or working process in downloadable form. Do you remember any of the best advice or specific rules from the corny guide? SS: The corny guide had a big section on “character-driven plot” that was really helpful to me. The idea that the story’s plot should spring from the character and their decisions, instead of figuring out the plot beforehand and plugging them in. It seems obvious now, but early on I would always try and think of the story as a whole, as something the character I would eventually figure out had to endure. It’s obviously much more interesting if the things that happen in a story happen because of the character’s choices. I still have to remind myself of this when starting a new story or novel. HAS: I do really love reading the “Art of Fiction” interviews in the Paris Review. I could read all day about which pencils writers like, and why, and how many stacks of paper it is best to have on your desk. I especially love reading about how such-and-such great story or book received dozens of rejection letters. These were among the pleasures of your book, too, as “Sam” deals with matters both theoretical and practical. And he faces a lot of rejection from publishers. Do you generally like shop talk? SS: Yes, and those “Art of Fiction” interviews are the best for that. I always want to see if there’s some practical or superstitious trick I can borrow that will completely change the way I write and make me more productive. I remember reading Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast and he talks about how he would always leave some work for the next day when he stopped writing—like, if he was working on a paragraph and that was the last thing he had to do before moving on to eat lunch, he would stop there so he could pick up on it the next day. As a way to keep the momentum going. I love that advice. Lydia Davis’s Essays One, which came out a few years ago, is amazing for this. She talks about where her stories came from and breaks down other writers' stories she admires. In one essay, for example, she recommends that writers take public transit because “(1) you will write a good deal more waiting for a bus or sitting on a train than you will driving a car; and (2) you will be thrown in with strangers—people not of your choosing.” HAS: You started writing songs before fiction too, right? Do you think songwriting was good “training” for your later work as a novelist and short story writer? SS: I did, yes. And the songs I wrote were stories. They were all like “The Pina Colada Song.” I think working in any artistic form will help you in some way when you move to another. One specific thing that I think carried over is, when I was writing songs, I would have to perform them in front of people and that made me a better editor. I would picture singing something in front of an audience and sometimes that would nudge me to edit things that didn’t feel quite right, like I could feel the slight embarrassment that would come if I didn’t change the words. When you’re writing fiction, you’re not really performing it aside from a few excerpts at readings now and then. But now, when I’m revising my work, I often imagine how I would feel reading what I’ve written aloud in front of people and it helps me see what needs to be cut or changed in some way. HAS: Let’s get into your new novel, The Cobra and the Key. First, I’m curious about your motivation to name your narrator/protagonist after yourself. Was this settled from the beginning? You are much more successful than your alter ego here! SS: I decided on this late in the process. I know the book says it’s a novel on the front cover, and the little bio in the back gives away that I’m different than the book’s Sam Shelstad, but I thought it would add to the effect of the writing guide being genuine. Blur the lines a little, I guess. And as you read through the book and see the narrator make horrible decisions, act selfishly, and dispense idiotic writing advice, I thought it would add to the joke if that narrator became somewhat mixed up with the novel’s real author in the reader’s mind. HAS: “Sam” has some good advice for us here and there, I think, but he often applies the truisms or cliches in preposterous ways, which is a big source of the humour. But one thing that I really admired about Sam, in the end, was his unflappable commitment to his work. He keeps going. SS: You’re right, it is pretty admirable! Writing is hard and you have to spend a lot of your time working at something that will possibly end up going nowhere, so it takes real commitment to keep at it. And no one really cares if you do it or not. Part of what makes a writer a writer is that, perhaps foolishly, they stick to it. HAS: On the other hand, whatever his strengths or weaknesses as a writing guide, “Sam” is an asshole in his real life, which interestingly we only learn about through his own oblivious narration. He doesn’t go to visit his septuagenarian girlfriend when she is in the hospital after a fall, for instance, because it would pull him away from his writing. Is there something about the nature of writing that can breed a particular kind of self-absorbed egomaniac? Musicians and theatre people at least have to work with others, usually. SS: The fictional Sam’s egomania is an exaggeration of behaviour I’ve witnessed in others, both writers and non-writers, but he’s not based on anyone I’ve met. If anything, he’s a caricature of my own worst qualities. Before my first book of short stories came out, I was shopping around a novel that everyone rejected. I remember feeling a little bitter at the time and jealous of other writers who had books coming out, and it was a pretty gross feeling. I’m glad now that the book never came out, but even if it were something I was still proud of, who cares? Just focus on the writing. But that jealous, bitter version of myself that existed at that time helped me tap into my ugly side and create this asshole of a character that I had a lot of fun with. So yes, I think there is something about writing that leads to this sort of self-absorption. You alone create something and the only way for other people to experience it, aside from putting it out yourself, is to find a publisher. Since there are limited spots available, there’s competition, and this can create bitterness and writers feeling like they are owed success, or whatever. It’s an awful space to be in, but also really funny. I’ve always loved comedy centered around delusional egomaniacs. HAS: What do you make of the idea that reading literature makes us more empathetic? Insofar as “Sam” is capable of self-awareness, he seems to achieve it through the process of interpreting/reading his own (autobiographical) novel-in-progress. SS: Reading fiction should make people more empathetic, right? It allows you to slow down and spend time in someone else’s headspace—both the character’s and the author’s. You interpret the world through someone else’s eyes while navigating some sort of narrative. But I know people who don’t read much fiction and are highly empathetic, as well as heavy readers who tip poorly and take up an extra seat with their backpack on crowded subway cars. The fictional version of myself has a weird relationship with literature, where I think he mostly uses it to justify his behaviour and indulge in fantasy. He reads into others’ work, along with his own writing, in an attempt to reframe his own decision-making and circumstances in a more sympathetic light. He writes stories to play out his own experiences with more desirable outcomes. But it’s true that what progress he makes in terms of becoming more self-aware comes from his writing. HAS: Yeah, it’s true that a lot of his reading also reinforces his own values and sense of self too. How has your own relationship to publication changed over the years? I can remember being almost desperate to write a book or to have written a book. I thought it would totally change my life. “Sam” is pretty good at adjusting his expectations as he goes along. SS: I try not to take having books published for granted and I really appreciate getting my stuff out there, but I’ve found the real pleasure with writing is still the actual writing. Like when you’re working on something and it’s going really well. Nothing beats that. Before my first book of stories came out, I think I had a similar feeling of desperation, that I just had to have a book come out. Because that’s obviously your goal if you’re a writer who has just started. But I’ve come to realize that I was already experiencing the peak of the writing experience from the beginning, right when I first started experimenting with fiction. Just making stuff. That may sound depressing or inspiring, depending on how you look at it. HAS: Your book before this one, Citizens of Light, was a detective novel of sorts, and this one is a writing guide of sorts. You seem particularly interested in genre, playing in and with the conventions of a field or tradition. I’m curious how much you think about these categories when working, if at all, such as crime versus “literary” fiction? SS: Maybe this goes back to your earlier comment about appreciating having rules when it comes to writing, but I think I just like working with constraints. With Citizens of Light, I had the character and her world sort of figured out and I also had the idea to set something among the tourist trap areas of Niagara Falls, but I had no story. The idea to take that character and that setting and turn it into something like a crime novel and make use of the genre’s conventions opened me up by placing all of these constraints on the book. I knew there had to be a central crime, and a procedural sort of tracking down of clues, and it would have to end with the central crime being solved. And then all of the other genre conventions I could play with, having this unusual (for a crime novel) protagonist and narrative voice and setting. By boxing yourself in like this early on in the process, you have to get creative in how you write something new and interesting within the confines you’ve placed on the work. The writing guide idea placed a lot of constraints on me: it had to be somewhat believable as an earnest writing guide (within the world of the story) and had to have a conventional guide structure. The constraint of having to shoehorn plot into this kind of book really opened me up. HAS: Any plans for any sequels to either Citizens of Light or The Cobra and the Key? Or, any other genres you are thinking of grappling with? SS: The idea of writing a sequel to Cobra sounds enticing, if only because writing the first one was so fun, but I think I squeezed all of the juice out of that idea. I’m working on a novel now that takes place in the early 20th century, so I guess I’m venturing into historical fiction. But so far it reads like all my other writing, I think. I’m doing all this research just to tell the same kind of story I’ve always been telling. HAS: I guess we could finish with a final process question. When I read your work, because a lot of it is very funny, I imagine you having a grand old time, laughing and typing away. Set the scene for us: Sam working on his first draft of The Cobra and the Key. Are you having a grand old time? How many stacks of paper on your desk, etcetera? SS: You’re not far off, with The Cobra and the Key. Usually I have good and bad writing days, like anyone else, and there are definitely times where it feels like a slog. But this novel really was a lot of fun to write. I wrote most of it while my wife was pregnant, and the knowledge that I would soon have much less time to write when the baby came lit a fire under me and I wrote it pretty quickly. It’s also a book that’s filled with jokes, and writing jokes is fun. I had one notebook that I kept on my desk throughout, which I filled up with notes and ideas. I had a small stack of writing guides on hand too, for reference. The book is filled with examples from other novels and short stories, so I would often run over to a bookshelf and grab something I thought might provide a good illustration for a writing tip that the fictional Sam could mangle. That’s something that made writing this book so enjoyable too: turning to random pages in novels I’ve read and finding excerpts that I could play off of. It gave the writing process a strange sort of collaborative feel, or like fate was involved, since what pages I happened to turn to dictated much of the content of the novel. Henry Adam Svec is the author of American Folk Music as Tactical Media, a scholarly monograph, and Life Is Like Canadian Football and Other Authentic Folk Songs, a novel. He currently teaches in the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Waterloo.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us