Mathew Henderson's RoguelikeReviewed by Julian Day

|

|

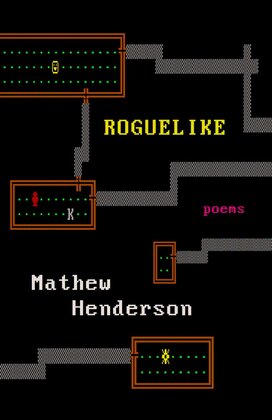

Where is the place for myth in the modern world? What do we tell ourselves about those we love, and how do we manage belief in an age of luminous technology? In Roguelike (House of Anansi Press, 2020), Mathew Henderson’s second collection of poems, the world becomes a mutable, breathing organism, a place in which myth and storytelling collide against the real. In Henderson’s poems, the living and the dead share a mutual and often computational space: physics follow from imperfect programming rules, surroundings become sprites and polygons, and the textures covering everything are taut and always threatening to tear apart.

This is a collection immersed in video games, informed by online vernacular and the particulars of this technological age: Roguelike takes its title from roguelike games, a genre of computer games loosely based on Rogue, first released for Unix in 1980 and ported to early home computer systems in the years thereafter. In roguelike games, the player takes the role of a character forced to navigate a hostile world for some loosely-plotted purpose. Originally envisioned by its creators as a kind of single-player Dungeons & Dragons, Rogue places the computer in the role of dungeon master, materializing the player at the top of a deep and randomized dungeon, tasking them with retrieving the mythical Amulet of Yendor. In the player’s way stand fantastic creatures and nagging hunger, forcing the player to dive deeper, the ultimate outcome being the amulet, starvation, or death. And death, in roguelikes, is permanent: the player can save their game and come back to it later, but after death, the savefile is erased, and the player is forced to start a new character again. While many roguelikes remain faithful to Rogue’s fantasy roots, a number of games in the last decade have branched out thematically, notably Cogmind (2015), in which you play a robot capable of building itself up in innovative ways through the use of scavenged parts, and Caves of Qud (2015), wherein you wander the strange and deadly wastes of a post-apocalyptic landscape. But in roguelikes, regardless of theme, the world becomes a kind of second, shadow character, both companion and competition, one in which the dead step out through walls, plants become sentient sources of information, and where there’s a chance you might choke to death on the food you find. The games themselves, however, are not the direct subject of these poems, and form instead a lens through which Henderson explores themes of addiction, family, and loss. In “Vana’diel,” the speaker experiences temporary solace exerting control over a character in the online world of Final Fantasy XI, before a cocktail of Nyquil and caffeine causes flashbacks to dealing with a mother’s addiction to pills; in “The Konami Code,” a suicidal woman saved by the speaker’s father in the distant past returns through the speaker’s closet, dripping wet, to tap out the Konami code on his sternum, imparting the possibility of something better. Henderson has a talent for the strong image, a sharp setup. In “In Midgar,” the title recalling the “In paradisum” (into paradise) of the Western requiem mass, he uses a plotline from Final Fantasy VII as a device to mourn a lost love, what might have been done differently, and what might have been: how a simple happiness, an earthly paradise, might have been found in the moments before destruction and ruin. Instead of leaving the doomed city and pushing on to the point where Sephiroth finds Jenova and eventually kills the flower-girl Aeris, the speaker envisions getting a group of people together to beat up Sephiroth out behind the gym, “like guys / would have done back in the day,” golf clubbing his kneecaps, settling things down to a violent and socially acceptable equilibrium. He concludes: |