Benjamín Labatut's The ManiacReviewed by Kevin Canfield

The arrival of When We Cease to Understand the World (2020)—the first of Benjamín Labatut’s books to be published in North America, and one of the more unsettling works of historical fiction to appear in recent years—introduced English-language readers to a fascinating writer, one whose precise, unhurried prose was perfectly paired with his subject matter, a partially fictionalized group portrait of trailblazing 20th century scientists. His protagonists’ laborious breakthroughs in physics and quantum mechanics redefined the limits of what could be designed and built in a laboratory, setting in motion what can only be described as a series of slow-motion catastrophes: the development of mustard gas and other airborne poisons, which killed tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians during the First World War, and the construction of atomic bombs, which killed hundreds of thousands of civilians when American planes dropped them on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the last days of the Second World War. The book, translated from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West, was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize and selected by The New York Times as one of the 10 best books of any kind published that year.

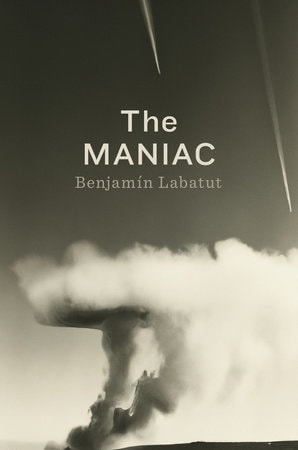

Labatut’s follow-up, which he wrote in English, is very much a companion piece. The Maniac, an attentive, chilling novel about real-life mathematician and computer scientist John von Neumann’s role as a military-industrial-complex ideas man and artificial-intelligence pioneer, cements the 40-something Chilean author’s position as one of contemporary fiction’s most astute chroniclers of creeping doom. Once again, Labatut focuses on seminal scientific work that has brought us “face-to-face with dangers that we may not have the knowledge or the wisdom to overcome.” From the outset, Labatut makes it known that he’s hunting big game, describing von Neumann, who was born in Hungary in 1903 and emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1930s, as “the smartest human being” of the last 100-plus years. In chapters narrated by characters based on von Neumann’s friends, wives and colleagues at two sites of fabled intellectual dynamism—the World War II bomb-building complex in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Princeton University’s Institute for Advanced Study—Labatut depicts his protagonist as conspicuously thrilled by technology’s potential for upending entire ways of life. We see him as a boy, disassembling complex machines just to see how they worked, “squeal(ing) with delight” upon learning that a Frenchman, around the turn of the 19th century, made a labor-saving loom, displacing workers and inciting societal strife. Decades later, Labatut’s von Neumann, by then an established U.S. Defense Department consultant, investigates how he might use a nuclear explosion to control the movement of storm systems, perhaps providing the military with the means to launch “a weather war that would make Zeus’s lightning bolts seem as innocent and harmless as the projectiles fired by a teenager’s BB gun.” At Princeton, after World War II, von Neumann built a room-filling machine dubbed the Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator and Computer. In the years that followed, various iterations of his MANIAC would run tests on everything from the destructive power of next-generation thermonuclear weapons to the feasibility of creating self-sustaining digital life forms. In his last years—he was 53 when he died of cancer in 1957—von Neumann “was dreaming of a completely novel form of existence,” writes Labatut, a species of “automata” with an insatiable reproductive impulse. The Maniac gives us a look at what purports to be von Neumann’s writing on the subject (but which appears to have been invented by Labatut):

Some readers will surely complain that the book doesn’t stay close enough to the documented facts of its subject’s life. Indeed, a person with preexisting sympathies for von Neumann is apt to consider The Maniac notably unfair, a compendium of unflattering biographical information assembled in a way that places the blame for so many of the 20th century’s scientific sins on the shoulders of one man. But this is a novel, not a work of rigorous scholarship, and to read it expecting the latter is to misperceive Labatut’s intentions, which evince a kind of mournful idealism. Though he’s beguilingly resistant to publicity and would probably contest such a notion, Labatut, as much as any writer working today, is building a unified artistic project based on an immensely important idea—the galvanizingly humanist assertion that we should be in control of the machines we build, not the other way around.

What happens when humans cede agency to impossibly complex tools of our creation? In When We Cease to Understand the World, savage devices are built and then deployed, not because there is no alternative to their use, but because, to cite one example, the Manhattan Project was arduous and extremely expensive, a feat of scientific engineering so impressive that its products—the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs dropped on Japan—accrued a kind of lethal momentum that neither the Pentagon nor the White House was able, or even tried, to halt. In The Maniac, Labatut considers the tension between humans and machines in a present-day coda to the von Neumann story. Titled “Lee or The Delusions of Artificial Intelligence,” this final section is about the real-life 2016 match between Lee Sedol, the world’s best Go player, and AlphaGo, a computer program that, after some helpful input from its development team, taught itself to play the intricate board game, which was invented in China 3,000 years ago. In short, the computer wins in a rout, surrendering just one of five games and enveloping its opponent in “a sense of despair, a strange feeling of being pulled down into a void, slowly but irrevocably.” Labatut’s account of the matchup will horrify anyone who doesn’t want human beings to spend perpetuity being bullied and replaced by artificially intelligent monstrosities that weren’t reined in when there was still time. No one would argue that all digital technology is bad (though if I have to read another novel in which text messages and, for fuck’s sake, emojis are reproduced on a printed page, I might soon get there). Like anyone reading this online-only book review, I could make a long list of the ways in which instantly retrievable information and continent-bridging connectivity has improved my life. But if you’ve watched drones fight wars on your cellphone screen, or talked to a teenager about their experiences with the demonic algorithms that govern social media, you know that there’s plenty to worry about. As one of this book’s characters puts it, we may be “approaching some essential singularity, a tipping point in the history of the race beyond which human affairs as we know them cannot continue.” Labatut’s eloquent works of fiction are based on a crucial truth: Our high-tech tools will continue to undermine our humanity if we let them. Kevin Canfield's work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Cineaste, Film Comment and other publications. He lives in New York City.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us