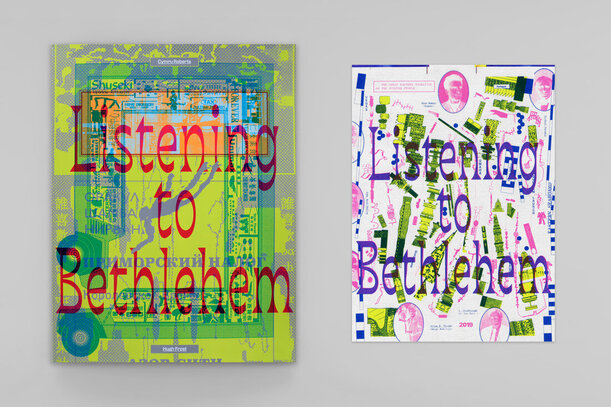

Cymru Roberts' Listening to BethlehemReviewed by Kiran Bhat

|

|

Rumbling, rambling sentences drive the reader across the panorama of thought and imagination that is present in Listening To Bethlehem. It is no accident that the title calls to mind the essay collection by Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, as the author Cymru Roberts himself overtly references Didion and her style at various points in the novel. However, while Didion aspired to portray the grime and grimness of a Counterculture California, Roberts aspires to create an almost drug-infused euphoria out of the dark lanes and alleyways of his Las Vegas. Much like Sin City, Roberts’ imagination is running in a cinematic gray, or a cartoon’s black-and-white, and it is in these delirious saunters that Roberts and his characters encounter not truth, not fulfillment, but the darkness calling out to them, encouraging them to err once more.

Roberts’ novel is rooted in the sojourns of four characters. The character who gets the most space to speak in the novel is Robertstein. We are introduced to him playing golf with a stranger who becomes a friend. He later visits his girlfriend Farah, and befriends her brother Farhad. He makes friends with a backgammon player a little later on in a Starbucks. Then, guilt, attraction, and self-loathing pull him back towards Farah. Robertstein seems constantly lonely and needy for human affection. He pulls himself into anyone who will give him time, he lives to make relationships out of anyone. Whether the people he meets are simply shades of a moment or result in real bonds is harder to glean. Such is the point. Robertstein’s roundabouts are rooted in an existential picaresque, which constantly circles back to him being unfulfilled, misunderstood, and alone. If the reader discovers empathy in Robertstein, they discover aversion and disgust in meandering hitman CK. CK tends to spout racist nonsense, go into long, self-indulgent rants, and kill innocent strangers. A perfectly hate-able gentleman, indeed. Once again, whether CK is meant to be a stand-in for any particular tendency or simply a manic creation of the moment is hard to tell. However, while CK kills, Robertstein self-destructs, the Russia-stuck Travis hallucinates in a closed environment in fragmented, surrealist prose, and the Eight Teens take to fighting good, evil, and themselves in eight different countries of the world. One thing is clear: each and every character represents a little bit of the fantasy that Roberts builds out of his ever-morphing Las Vegas, and the seeds of discontent or disarray that spring from his native city. From a craft standpoint, Listening To Bethlehem impresses on various levels. Certain images like the following |