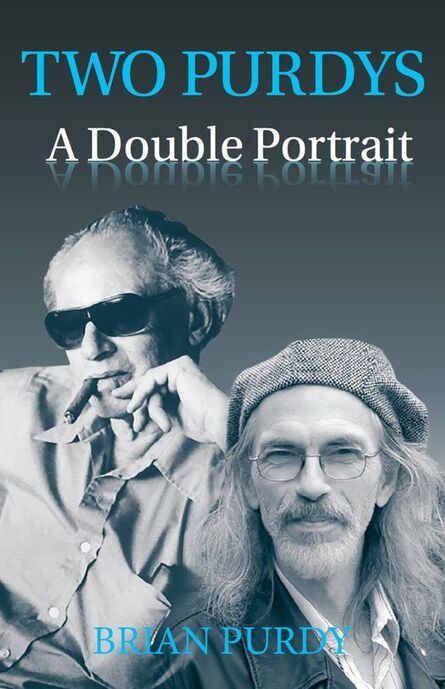

Sharon Berg Interviews Brian PurdySharon Berg: Thank you, Brian, for agreeing to do this interview with me. I think it’s fair to say that Two Purdys: A Double Portrait has been a long time in germination. Some would suggest it brewed in you since your childhood, and the fact is that this book was put together and arranged into six sections—three essays and three sections of poetry—in 2016. (Full disclosure: It rested unchanged until 2022. I know this because I helped to produce the manuscript.) Can you share why you think it took so long to get back to working on it, so it could become available to the public?

Brian Purdy: For better or worse, my attitude toward the passing of time is lackadaisical. I simply trust that I will be here on earth long enough to finish what I wish to accomplish. After a given project matures to completion and has been shared with friends, if wider readership takes longer or shorter to accomplish this matters very little to me. While publication in solid venues either on line or in print is desirable, this is not the end goal. In fact, for me, the making of poems is central. Sharing these with friends and new acquaintances is second in importance. Publication in print merely extends readership and numbers are not really the goal. Not only that, but I find commonly-used words like ‘submit’ and ‘submission requirements’ grounds for rebellion. I would prefer to make my presence and my work quietly but firmly evident, so that it says ‘here I am; come and find me.’ Of course, that attitude is profoundly impractical. As Robert Frost says, ‘The unworldly are forced to be worldly in self-defence’. SB: Why did you decide to name the poetry sections in Two Purdys after parts of the A-frame property in Ameliasburg, which has become a popular writing retreat since your father, Al Purdy’s, passing? BP: Naming the sections of Two Purdys after elements in the composition of the A-frame property seemed natural once suggested. With the help of several others, my father fashioned the place with his own brain and body; thus it was very closely identified with him. Robert Graves fashioned his own furniture for his writing room in Majorca back in the 1930s so that all aspects of the place would be harmonized with his activities. Whether he intended so to arrange for himself, Al did much the same. Also, in the making of these divisions in the book it felt to me as though various groups of poems were assigned to different areas of Al’s physical body—or to different parts of his awareness of his surroundings in life. Again, to do as was done felt ‘natural’. SB: Though poets have created memoirs of their parents in verse before (e.g. Pablo Neruda) this is an unusual book for several reasons. Much has been said in recent years about Al Purdy building a specific public persona. In addition to memories of building your relationship with a famous person, Two Purdys unravels your personal relationship with him, a relationship painfully ignored through the public persona of Al Purdy. His public face really didn’t match up with his private face though, did it? BP: For the most part, in my case, Al’s private face was turned affectionately in my direction. Though not frequently available in person he took pains to maintain regular correspondence with me, even when, for periods of time I failed to inform him of changes of address or was negligent in answering his letters. He introduced me to friends, both famous and otherwise. He scouted volumes for my used book shop, carried them up three steep flights of stairs to gift me with them—was generous always with beer and books. His private generosity cast his public lack of recognition of either Mother or me into very harsh contrast. Nevertheless, I knew he cared for me as his son. Interestingly, when his collected letters were published I found therein a single letter addressed to me. It was as though he meant its inclusion as a clue for future literary detectives—his final acknowledgement to his public readership of the father/son relationship between us. SB: In terms of audience for the book, there will be a group who are naturally drawn to reading this book, and others that you think should read this book. Are those two groups different? Why do you think the last group should read it? BP: To some degree at least, my father has become an icon for those who revere and value the qualities for which he stood. That is true particularly for his steadfast concern for the well-being and future of his native land, Canada the beautiful. This is a wonderful legacy—but, to my knowledge, no-one has yet taken on the full portrayal of Al Purdy’s life story. This is surprising. Others of his time and similar status have been honored in this way. I feel that my work in Two Purdys offers anecdotes, insights, images and quotations that body-out the private man and offer useful materials to whoever will, eventually, come to grips with Al’s story in book form. I look forward to that event and hope I am alive to read it when it is written. SB: Are there any questions that you feel this book leaves unanswered about the topics it addresses? What are they? Do you foresee a sequel to this volume? BP: I have come to understand that Two Purdys skimps proper notice of Al’s generosity and his capacity for love. I ought to have understood and paid fuller tribute to these elements of his character. The very last poem added to the manuscript was written and reached my publisher in the final stages of the book’s production. To some slight degree that poem (ironically enough entitled, ‘A.W.P.: as Petty Thief’) as well as this interview, have allowed me to redress my negligence. Should the book see a second printing I will do still more renovation. SB: Is this a book that seemed to lay itself out on the page quickly, almost as if it were channeled, or did you put a lot of effort into its structure and the developmental process for it? Please elaborate. BP: Purely channeled. SB: Is there a certain book, a collection of works, or a literary movement that inspired you to begin the work to map out this book? Please elaborate. What was the initial inspiration, even if that is something that should oppress writing on this topic or in this style? BP: I have no recollection of what books I read while Two Purdys was in gestation. However, I keep certain volumes well within reach. These include: Philip Larkin’s Complete Poems; Robert Graves’ Collected Poems, an edition from 1977 done by Doubleday; Mary Barnard’s translations of Sappho’s poems; Basho’s Narrow Road to a Far Province; Hemingway’s Complete Short Stories, Finca Vigia edition; The Voice that is Great within Us, American Poetry of the 20th century, editor Hayden Carruth; Jorge Luis Borges, Selected Poems; Leonard Cohen, Stranger Music; and Beyond Remembering, Collected Poems by Al Purdy. These are ‘the light-houses’. SB: Many people say that an author is never really finished with their work and would always wish to adjust and tweak their writing. Do you feel that way about this book, wishing you could change something? BP: This book continues to grow and accumulate more poems, more pages. It seems likely that it will never stop growing until my final day. Not only that, but since its first inception it has gone through literally hundreds if not thousands of alterations. It is difficult really even to hand it over to the publisher as ‘finished’. Even after publication, I will probably continue to refine my ‘product’ as new ideas occur to me. Paintbrush and palette in hand, the painter, Pierre Bonnard used to revisit his work where it hung in public galleries. Gallery attendants were warned that this might happen. I understand perfectly Bonnard’s compulsions. SB: How do you think this book should be assessed for its value? Does it offer practical points for further exploration? describe an important cultural event? offer a compelling message about a social shift? or does it describe your aesthetic? BP: Good heavens, I don’t decide or even speculate on the value of my stuff. Practical points? Nah. Just trying my best to suggest how it felt to know and spend time both with and apart from a remarkable human being about whom I had profoundly mixed feelings but learned to love as well as I was able. I only wish I had fully realized when younger how much he actually loved me. SB: How did you describe this book to a potential publisher before you began work on it? Or did you complete the book before you began approaching publishers? BP: This book, for the most part, was completed six years before it was accepted for publication. At the outset it did not say, ‘Do you want to write a collection of poems about your father and yourself?’ It said: ‘Here’s the core of an entire book, twenty-some-odd rough drafts boogying down main street tail to trunk, horns honking and guitars wailing. Unlimber your tool kit and grab a pew while they’re hot and don’t even think to quit before the show is over !!’ I did as I was told. An occasional elephant still sways past my front porch to this very day. I climb aboard. SB: How does this book fit it the stream of all of your literary works? Is there some fundamental difference between this book and your prior work? BP: Among my books, this one is unique. It is unlikely I will ever again devote an entire volume of poems to a single person. Always before, my collections have been a potpourri in nature and complexion. Sometimes they have limited themselves to single subjects, yes, but only this once to a single individual and my involved relationship with him. Closest comparison would be work I’ve done on E.A.Poe, which amounts to two short stories and several poems, one quite long, 200-plus lines. Still, nothing has been comparable in length and scope to the work done in Two Purdys. I have, however, written many verbal portraits of both famous and more ‘everyday’ kinds of people. A selection of these was published in 2016 by Big Pond Rumours Press under the title, Black Ink: Portraits. Sharon Berg is a poet, a fiction author, and an historian of First Nations education in Canada. She's published her poetry in periodicals across Canada, as well as in the USA, Mexico, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, India, and Australia. Her first two books were poetry published by Borealis Press (To a Young Horse, 1979) and Coach House Press (The Body Labyrinth, 1984). This was followed by two audio cassette tapes from Gallery 101 (Tape 5, 1985) and Public Energies (Black Moths 1986). She also published three chapbooks with Big Pond Rumours Press in 2006, 2016 & 2017. Her fiction appeared in journals in Canada and the USA. Porcupine's Quill released her debut fiction collection Naming the Shadows in the Fall of 2019. Her cross-genre history The Name Unspoken: Wandering Spirit Survival School was published in 2019 by Big Pond Rumours Press and received a Bronze 2020 IPPY Award for Best Regional Nonfiction in Canada East. She lives in Charlottetown, Newfoundland, Canada.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us