Sharon Berg Interviews Blaine Marchand

Sharon Berg: Blaine, I want to thank you for agreeing to do this interview with me. In Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry, you’ve reached backward in time to draw on the history of your family and your childhood memories, remembering both good times and sadness. It struck me as I read your poems, childhood poverty and strife can offer details to a memory that riches never seem to serve up. Do you feel that using the lens of poetry allows you to access details in a way that other mediums, such as strict prose memoir would resist?

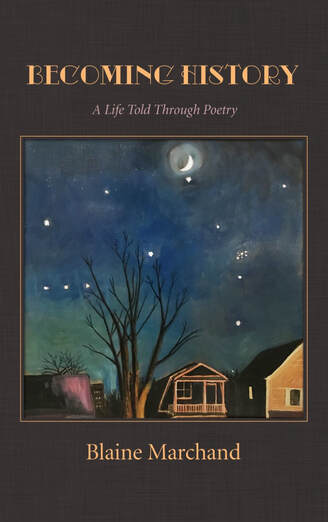

Blaine Marchand: I think my ability to remember things was inherited from my mother, who had amazing recall of details in her earlier life. She was a storyteller, vocally acting out incidents from her past. I remember things very visually and in great detail. Sometimes I wonder why. As a child, I wrote stories in a notebook. My grade seven teacher was the first person who told me I could be a writer after reading a class assignment I had done. She loved poetry and recited it to us. This enthralled me and made me realize the power that imagery possesses. So, I began to write poetry. I think poetry brings with it the ability to weave emotionally-charged memories through words. There is something in that type of voice, an honesty, an openness. SB: I’ve only encountered one other book similar to Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry, in that it offers a biographical portrait of a family member who has passed in verse. In her review of your book for Toronto Star (2021/09/30) Johanna Zomers quotes you as saying, “In a way, the book is about my mother’s life but also about mine and how I was shaped.” Brian Purdy says of his book, ‘Two Purdy’s: A Double Portrait’, “These are a son’s poems for and about his father. At the same time, they are a poet’s word portrait of another poet— ” (Pottersfield Press, 2023). It appears that you’re both on similar paths in painting your parents’ portrait, choosing to do your biographical memoirs as verse. Can you speak to your reasoning, in choosing to offer your recall of your mother’s life in verse? BM: My mother and I were always close. Not sure why as there were eight children in the family. In fact, I think each of the five boys had a close relationship with her but differently based on our personalities. That said, today when my siblings and I communicate via e-mail, as we are spread out across Canada and the world, it often relates back to our mother and rarely our father, perhaps because her death is recent while his was 42 years ago. My mother was proud of my writing and my poetry. Perhaps her talking to me about her early life was a way she indicated that she wanted me to write about it. It seems she did not talk about her early life to my other brothers and sisters. I always thought my elder sister, being the first child, would know the details of my mother’s earlier life. But she did not. It might have been because I was curious about my mother’s life and when she told me about different episodes, I asked questions. Is there always one child in a family who is like this? As I indicated, she was a born storyteller and perhaps she recognized this in me too, although I do it through poetry. When she recounted her earlier life, it really brought to life the various decades of Ottawa’s history. And I liked this very much because more often than not these things get forgotten over time as stores close and buildings are torn down and neighbourhoods change. Each generation recalls only what they have experienced in their timespan. I also wanted to capture her life for my son, grandson, and my nieces and nephews and their children. My mother was a remarkable, warm woman to whom people were naturally drawn. She had spark and verve and these incredible pale blue eyes. And she retained this to the very end. SB: In terms of audience for the book, will there be a group who are naturally drawn to reading it, and some you think probably should read this book? Are those two groups different? Why do you think the last group should read Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry? BM: The one consistent thing that people comment on in this collection is the vivid recall of memories from past decades—by my mother as well as by me. As it is set in Ottawa and in the neighbourhood I grew up in and in which I still live, it has special appeal to others who live here. But I also think that people my age group (the Baby Boomers) are caring for elderly parents and coming to terms with placing their parents in long-term care. My mother lived in the family home until just before she turned 101. She had a zest for life that she retained until the end. As she said to me three days before she died— "I have had a long and lucky life. I can’t complain.” The head nurse at the residence told me that people who live past 100 share that engagement with the world, remain optimistic and positive. I think these are qualities that all generations need to think about instilling in their lives as they age. SB: Titles are often difficult to come up with, though some authors seem to begin there. What was your experience in developing a title for Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry? BM: I did not come up with the title in the initial stages of writing. But the first section I wrote was about my mother going into long-term care. The poems about her death came later in the process. When I wrote the poem “A Cappella,” which had “Becoming History” as its original title, I knew that would be the title. So much of the book is about the history of my mother’s life and my own that is seemed to be a perfect fit. I initially thought of archeology when writing this collection—sifting through old photographs and memories and stories and how archeology is the uncovering of history. In discussion with Allan Briesmaster, the publisher, when I explained the book was a life told through poetry, he suggested it would be great to add that to the title. SB: Did Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry lay itself out on the page quickly, almost as if it were channeled? Or did you put a lot of effort into it? Could you elaborate? BM: As mentioned above, the book really began with the last section when I visited my mother in a long-term care facility when she was 101. Up until then, she had lived independently in our family home. When visiting, she would tell me stories about her early life with the family that took her in. As often happens late in life, our early years take on an urgency and poignancy. This led to the first section about her early years. After that I began to write about my childhood years. When I realized she was absent from these poems, I began to think about times as a child when I learned but did not fully understand her upbringing. As a child, I liked to hang around when people came to visit, such as her birth parents. She preferred me not to be there but even when shooed away, I lingered by doorways. My books are mostly thematic. I seem to write that way. Initially it is not clear that they are connected. But as I start to assemble the manuscript, I see what I have been exploring and begin to write poems that fill in the story. These are not always deliberate. Most times, the poems come seemingly out of nowhere but are obviously a response to my telling. So yes, once I discover the theme, I take the effort to make the book cohesive. SB: Books are often turned into television shows, movies, or radio scripts. They are also frequently translated into other languages. What would you say is the key point about Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry that should not be lost if it’s converted to another form or language? BM: If it were turned into a film, TV show or radio play, I would hope that its setting in Ottawa would not be lost. This is very important to me as we all are shaped by our early childhood and the places we lived and grew up in. Some people have said it is too Ottawa-focused. I find this odd. We do not say this about books or movies set in New York or London or Paris or even in Afghanistan. We allow the work to take us there imaginatively and experience the lives being lived there, even when we have no first-hand experience in those cities and countries. In a way, my work has always been shaped by places I have been. I have been extremely lucky in that my work took me to countries most people have never experienced. And I try my best not to write “postcard” poetry although the poems are through the prism of my imagination. I have learned a lot about life and how we experience things from my meetings and friendships with people from elsewhere and their values. And I am thankful for that. SB: Something that often interests readers is knowing how much of a certain work is invented and how much is autobiographical. Would you care to share your approach/thoughts on this aspect of your readers’ curiosity? BM: This is a good question. In terms of my book, I think it is clearly autobiographical but to a certain extent invented. Sometimes you need to tailor the poem so it clearly captures what you are hoping to achieve through it. You give it a setting. For example, in the poem “Equations,” where I learn about my mother’s birth parents, she was doing the dishes at the sink and had taken off her rings and put them by me on the table where I was doing my homework. I noticed the inscription on the inside of the engagement ring and asked her why her family name was different from her parents’ name. And she told me. Whether I was doing a math assignment I do not recall, but the idea of doing a subject that was difficult seemed to fit the mood I was trying to achieve in the poem. As is often said, poetry is thought well expressed, so invention is sometimes necessary. SB: How do you think Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry should be assessed for its value? Does it offer practical points for further exploration? describe an important cultural event? offer a compelling message about a social shift? or does it describe your aesthetic? BM: I find it hard to assess the collection’s value. But I do think it explores a life over almost 104 years and the many world events that took place during that time and shaped my mother—the Great War, the outbreak of diphtheria, the Depression, women not being able to work once they married, etc. I also think it reveals her background—abandoned by her birth parents, raised by a loving, older, working-class couple, and her parents suddenly coming into her life after her marriage—how she, as a woman, was able to find her way in the world and develop the philosophy of ‘live and let live’. The book very much is a reflection of my aesthetic. Not only my attention to detail and image (which for me is the very lifeline of poetry) but one shaped by family dynamics and how we learn to live with them. You asked about growing up poor, which for me as a child was never considered. My parents owned their own home; my father had a full-time and good-paying job. But I was the sixth of eight children, so perhaps it was different for me than my elder siblings who were born early in my parents’ marriage when money was tight. But my parents were both resilient and loving, so it was a stable home life. With eight kids, there were squabbles and fights but that is natural. SB: How did you describe this book to a potential publisher before you began work on it? Or did you complete Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry before you began approaching publishers? BM: As the work was complete, I thought the title of my book explained the content of the manuscript to publishers. This is because, over my career, with the exception of my first collection of poetry, I have always submitted complete manuscripts. Because my poetry tends to be thematic, I work hard on this aspect and attempt to pull it all together before submitting it. That said, I do workshop poems with Ottawa writer friends, most recently Susan McMaster and Colin Morton. I also have hired a poet to work as an editor of the manuscript. In the case of Becoming History, it was John Barton. In the past, working this way seemed to lead to quick acceptance. However, this was not the case with Becoming History. I tried a number of publishing houses but got no takers. I then submitted it to Allan Briesmaster at Aeolus House and he took it immediately. I was not certain why others were not interested but I assume there are many young poets coming to the fore and the literary landscape is very different than it was when I started writing. This is as it should be as Canada today is a very different and much more diverse country. But I always remember Dorothy Livesay, with whom I was friends, telling me that as she aged finding publishers became more challenging for her. And she railed against it. SB: How does this book fit in the stream of all of your literary works? Is there some fundamental difference between Becoming History: A Life Told Through Poetry and your prior work? BM: Although my books have always been thematic, what I have explored has differed, even though all of them have been for the most part autobiographical. If I group them, three were written in response to my travels to the developing world— Open Fires, my work in about 15 African countries, Aperture in Afghanistan and in a chapbook, My Head, Filled With Pakistan. Two of my books have a specific gay focus— Bodily Presence and The Craving of Knives. My third book, A Garden Enclosed, was about my wife’s illness and death from cancer when we were in our 30s. So I guess in a way, Becoming History has echoes of A Garden Enclosed. But I hope it is a fuller and more mature examination of life and death. Blaine Marchand's poetry and prose has appeared in magazines across Canada, the US, New Zealand and Pakistan. He has won several prizes and awards for his writing. He has seven books of poetry published, a chapbook, a children's novel and a work of non-fiction.

A selection of his poems about Pakistan, where he served as a diplomat, was published as a chapbook, My Head, Filled with Pakistan, in November 2016. His seventh book, Becoming History, was published by Aeolus House in 2021. He is currently completing his newest collection of poems, Promenade. Active in the literary scene in Ottawa for over 50 years, he was a co-founder of The Canadian Review, Sparks magazine, the Ottawa Independent Writers and the Ottawa Valley Book Festival. He was the President of the League of Canadian Poets from 1992-94 and was a monthly columnist for Capital XTRA, the LGBTQ2S community paper, for nine years. Sharon Berg is a poet, a fiction author, and an historian of First Nations education in Canada. She's published her poetry in periodicals across Canada, as well as in the USA, Mexico, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, India, and Australia. Her first two books were poetry published by Borealis Press (To a Young Horse, 1979) and Coach House Press (The Body Labyrinth, 1984). This was followed by two audio cassette tapes from Gallery 101 (Tape 5, 1985) and Public Energies (Black Moths 1986). She also published three chapbooks with Big Pond Rumours Press in 2006, 2016 & 2017. Her fiction appeared in journals in Canada and the USA. Porcupine's Quill released her debut fiction collection Naming the Shadows in the Fall of 2019. Her cross-genre history The Name Unspoken: Wandering Spirit Survival School was published in 2019 by Big Pond Rumours Press and received a Bronze 2020 IPPY Award for Best Regional Nonfiction in Canada East. She lives in Charlottetown, Newfoundland, Canada.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us