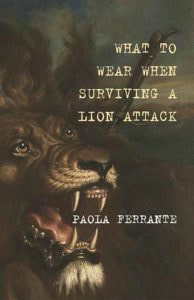

Paola Ferrante's What to Wear When Surviving a Lion AttackReviewed by Manahil Bandukwala

|

|

Paola Ferrante’s debut collection What to Wear When Surviving a Lion Attack holds nothing back as it goes through the violence of living in a patriarchy. From folktales to literature to horror, Ferrante crafts vivid poems that dig into discomforting histories that bleed into the present.

Heavy with symbolism, an early poem in the collection, “Wedding Day, Circa my Mother,” draws a comparison between a bird and a bride. Legacies of bridehood and motherhood share the colour white: “But in white she was beloved, whether white / was wedding dress or sheet or shroud.” Wife, mother, corpse: these are the expectations, the roles to fulfill, that Ferrante breaks down in the book. The poem ends, “A wife is not a bird; she does not fly / upstairs. She settles / down, becomes / a black hole, / collapsing in / on herself.” With these lines, Ferrante provides a disclaimer to the ways in which she will connect histories and geographies of violence and patriarchy in the poems. She uses analogies and metaphors to express the difficult legacies of trauma, but she also affirms that violence is not a metaphor. These two lines of thought persist in the duality present across many poems in the collection. Whether or not you come into this book with a visualization of what duality means, Ferrante’s poems will leave you with a broader understanding of the multiplicity of violence, of dangers, and of traumatic legacies. Ferrante starts the poem “Doppelganger” with these gripping lines: “It took me a long time to live / with my cunt like / Frankenstein’s monster, the one / no one remembers / by name.” There is a hilarity in the play on contemporary misconceptions that Frankenstein is the monster rather than the doctor, and this is juxtaposed with the cruelty enacted against the monster by the doctor, including stripping it of its identity. Situated in the legacy of Mary Shelley, who had to negotiate her own success against that of her husband’s, “Doppelganger” adds in the violence of sidelining women’s successes and foregrounding men’s. “As Told During a Routine Police Investigation” delves into the story of One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of folktales whose narrative arc depends on the instability and anger of King Shahryar. The poem draws a connection between the mother storyteller and Shahrazad. Ferrante writes, “Girls turned to dogs, then bitches, whipped, / when forty or thirty-three thieves stole / one thousand days and nights.” Women transformed and time stolen through violence threads together centuries and spatial distance. Ferrante excavates the domestic abuse behind Shahrazad’s stories and brings it to the forefront. Another fictional character Ferrante enters is Gertrude from Hamlet in the poem, “When Reading Hamlet in my Thirties I Answered for Gertrude.” “Let’s not pretend / it’s not a question of to be / or to beget,” she writes, twisting Hamlet’s famous soliloquy to talk about the tension between abortion and the pressures to procreate. Using a collective “we,” Ferrante draws on a lineage of dangerous methods to induce abortion because the alternative, rearing a child, means giving up a sense of agency. The pain of the procedure comes through in the lines, “all tears and blood and milk, / no honey,” disrupting the stigma of selfishness that surrounds abortion as the speaker chooses the physical pain of abortion. In addition to articulating the abuse meted out against real and fictional women, Ferrante also explores violence and pursuit as it appears in animals. In “The Mere Exposure Effect, or How to Make Men Like You,” she writes the transformative journey of an octopus after relentless stalking from a lionfish: |