Interview with Síle EnglertInterview conducted by Kevin Heslop

|

|

This conversation took place on 29 July, 2019 in London, Ontario. It has been edited for length and clarity.

So, I thought we might begin by discussing Threadbare, which takes its epigraph from Carl Sagan: “For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.” Thinking about “Functional Interpretation of the Knee,” “An Exoskeleton is Not the Same as Armour,” even “Diphylleia” and your ongoing series of phobia poems, nomenclature exemplifies the precision of your use of language. I wonder if you’d talk a bit about the synthesis of science and language in your work and where these two ostensibly distinct disciplines––where facts readily become opportunities for metaphor in your hands––fused in your experience.

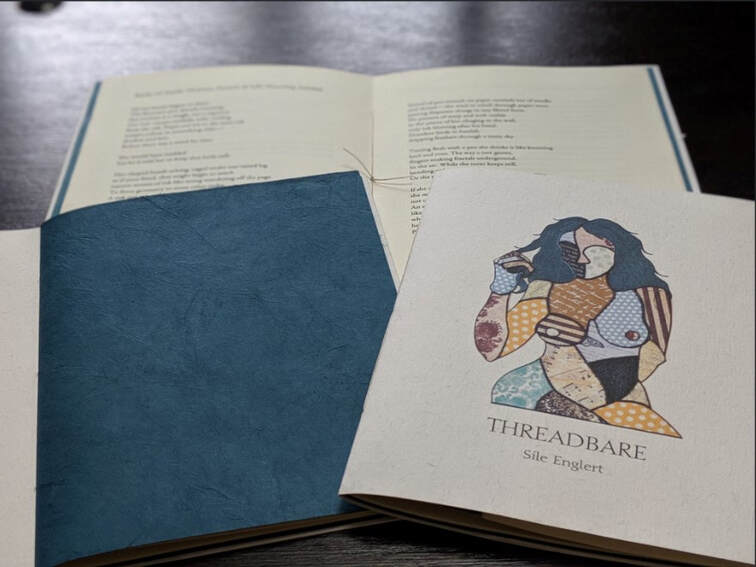

I think it’s interesting that we think of them as so different, science and language, science and art. The way I look at it, there is a lot of poetry to be found in science. And when I was younger, I was just ravenously interested in everything––from dinosaurs to the cosmos to planets to evolution; and I read more science fiction than anything else, and I think I still do. And if I watch a documentary or read non-fiction, it’s always science- or history-related. So, I had that passion, and when I got to high school, taking science classes became less accessible to me because I’m terrible at math: numbers and I don’t get along well at all. And so when math became a bigger component of learning science, it turned into an either/or. My strengths were in language and art and history. I didn’t stop reading, I didn’t stop learning on my own, but I couldn’t pursue it. And I think it wasn’t until I met my wife Liz that that was reawakened. It was the way she sees the world. When I met her, she was doing her master’s in physiology, and she had just done a double BA in physiology and English language and literature. So she has one of those rare brains that can do both, and I thought that was fascinating, the way that she sees things. She can look at a poem and analyze it and critique it and she can go into the lab and do experiments on brain cells; I just thought that was amazing, and it gave me a bit of a push to explore a passion for science through my art when I couldn’t find any other way to do it. And not unfamiliar to you are the textbooks that she reads? Do you incorporate her area of study into yours to an extent? For sure, yeah, because it’s what we talk about. And because it blends into poetry, a lot of what she’s doing ends up in my work. So, I kind of feel an obligation to get the apocalypse question out of the way early on. *laughs* And then we can narrow the focus a little bit. It’s always there, hovering. Yeah, so I guess speaking of the blend of language and science, we both recently listened to the audiobook version of The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells. And so this is potentially a stillborn and far-too-big question, but I wonder how you think of the artist’s obligation in our moment, and whether that is different from what it has ever been. Do you feel a personal obligation to address directly, through your art, questions of the sixth mass extinction and environmental collapse, or is it more something that’s naturally infused in your work as a result of it being in the ideological air at the moment? I think, for me, it’s not so much an obligation as just inevitable. I think art and writing can’t help but be a reflection of the time that we live in, even when the artist sets out purposely to do the opposite. There’s always going to be echoes of what’s going on––socially, politically, environmentally. There’s always going to be the artist’s emotions infused with that. So, whether you have to or you want to, it’s going to show up in your art no matter what. So I think a lot of us, especially creative people, are existing in this existential dread right now, or feeling a sense of impending doom and heightened anxiety. And I think that’s coming up more and more in what we write and what we create and how we live. Okay, well now that that one’s out of the way, can you talk to me about the choice of “Threadbare” as the title for the chapbook with Baseline Press? Actually, I guess the short answer to that one is that it came out of a line in a short story that I wrote. There was a line where I chose to describe my character’s voice as sounding threadbare––I used it as the adjective for the voice. And it was a good fit for connecting all of the metaphors I used through the poems of textile art and stitching, knitting, quilting, sewing. And it brought together the idea that I’ve done with the collage on the cover of a kind of patchwork person who’s a work-in-progress and made up of all the experiences they’ve collected along the way––all of their joys and all of their pains. So, that word stuck with me after I wrote the story and I needed to do something else with it. Yeah, so this idea of a patchwork person or identity could maybe also be a metaphor for the variety of artistic disciplines that you take part in, yeah? Definitely. I have trouble sticking to one thing. I have so many passions and so many things that I’m interested in and curious about––things that I want to try. What’s something that you ventured into recently that was rewarding in one way or another? The animations that I worked on last year were very recent, very new for me. I’d never tried anything like that before––nothing on that scale that required so many small pieces. I do a lot of very tiny, intricate, careful work, but it was a completely different medium for me; and it’s something I’ve always been interested in. I love stop-motion; I enjoy stop-motion movies and music videos and things, and I thought, I’ll see what I can do with this. It was amazing to break it down into tiny, individual pieces and build it bit by bit. I had to cut all these tiny bits of paper, and it took hours and hours, but I enjoy that kind of work––that careful, monotonous, detailed work. I rewatched the stop-motion video that you did to accompany Yessica Woahneil’s song, and there are dozens of uniquely cut fish, and really clever details that I found in, for example, the movement of fish: when they were going in one direction they looked one way, and then it looked like you inverted them when they went the opposite direction. Extremely careful, precise work. I find the movement of stop-motion fascinating. We think of movement as something very fluid, and when you break it down into stills that are just pieces of seconds, it kind of turns it into a different creature altogether. Is there some metaphor to be drawn between poetry and fiction there––the difference between a still and a sequence of stills? Maybe the better question is: How do you conceive of the distinction between poetry and prose; and what tells you it’s a story and what tells you it’s a poem? I think that I don’t often know the answer to that, and I often get it wrong the first time. I might start out with something that I think is a poem, and it grows and it grows, and I look at it and think, Oh, no, this is supposed to be a story. And I think part of that has to do with the way literature is changing, because of the freedom we have to experiment more and more. The definition of what a poem is and what a story is is changing. I think the idea for me is to learn the traditional rules very well, and then smash them to pieces. Mm. People are pushing the boundaries and changing what we are able to do in each form. So I think with poetry it’s almost a smaller slice of time; it’s more like a moment, or a piece of a moment, that you can expand and dwell on any detail you want, and it works. With a short story, it often has to be something broader and you have to choose your details more carefully. Can you riff for a second on what the increased freedom in terms of how we conceive of a poem is? I guess historically there are limitations in terms of the structure, and what’s permissible as a line, or line break. In what way has freedom manifested in the poem? I think that there’s a lot more space being made for artists to push themselves creatively and push their skills in different directions. Working inside a traditional form now is kind of an unusual thing to do, you know? If you start working with rhyme or a certain number of syllables in a line, that’s become different and strange. And so doing that––giving yourself constraints––is sometimes an interesting exercise. But I also think that having the freedom to expand all of that and to break lines in places that you wouldn’t expect and use words as verbs that aren’t verbs, and just push and blur those lines and create something very new. I think there’s something to be said for both, for both following a form, and just smashing it to pieces and taking it in a completely different direction. That feels sort of entropic, maybe. Yeah. I’m wondering if there’s a parallel between the advancement of human civilization and the way that that manifests in the development of art forms. I think the funny thing about poetry too is that it is a very careful disorder. Even when it looks disordered, there is so much thought and detail and careful attention to every syllable, to every period, to every piece of punctuation. There’s a lot of contrast there that I like. So, appreciating the spaciousness of what’s possible with a poem today, I feel like there’s a consistent fidelity to narrative in your poems. Do you agree with that, and if so or if not, how else would you characterize a poem that you’ve written? I do agree with that. It’s interesting to me that they come out like that, because, on one hand, I’m a little obsessive about symmetry. I find comfort in order; I like things to have a shape. That’s not how I work. That’s not how I create, but that’s how they always end up. When I start something, it starts with just a little seed––a word, a shape, just a small idea––and it sort of grows organically in multiple directions. To finish, I usually have to pare down and cut it back and it almost always ends up being something in a clear shape, even if that shape is a spiral. So, this idea that they grow in multiple directions and that at a certain point they have to be pared back, and your use of the word organically, it feels like there’s a sort of horticultural way that you conceive of writing––does it relate somehow to plant growth? It does for me. I see a lot of things as interconnected systems, like a root-network. I’ve used that in poetry before. Yeah. And it’s how I see my art, how I see my writing: it often starts from one point and grows like that, branching with all these little tributaries. You could it take in any of those directions, and it depends on what you choose, how it ends up. Right. It ends up being a lot more ordered than I expect it to be from my work style. Which looks like what? Kind of a disaster *laughs*. If it starts with one word or one sentence and ends up looking like something branching out, like a mess––things going in every direction. And then I think I spend the most time chopping it up, paring it down, dividing the lines, trying to figure out where everything goes. I start with a mess of random lines and words and when I’m finished, it ends up being something very clear, very linear. I’m thinking of the line attributed to Valéry that a poem is never completed; it’s only abandoned. Mhmm. Do you identify with that? How do you know when a poem’s finished, or do you know when a poem’s finished, or are they ever finished? I think it would be very easy to keep fussing with it until you lost the essence of it entirely, so at some point you just have to give yourself a talking-to and say leave it alone. Usually, when I get the sense that it’s ready for feedback from other people, and once I incorporate that feedback, then I probably won’t make any more big changes unless it goes through an editor to be published. Right. So, I don’t know if they’re ever really finished or you ever really feel completely happy with them, but if you mess with them too much, you run the risk of damaging them, I think. Um, at the risk of tainting your ability to give an objective, sober analysis of what workshops do for you––considering that I’m a participant in one of them––I’m wondering if you could give a really down-the-line sense of what workshops have done for you. I think you’re in two, right––one in poetry and one in prose? I think for me, because writing can be such a solitary exercise––you end up spending a lot of time in your own head and your own thoughts. And as much as I want to experiment and push myself and push my creativity––I also need people to challenge me. I need people to say, this part doesn’t make sense. Or, that word is wrong. Or, I feel like you could take this further. I think it’s extremely valuable to have several other sets of eyes to look at your work in a fresh way, especially when you’ve spent a lot of time on it. I think I’ve said before that I get to the point where I can’t tell if it’s genius or garbage anymore. I’m looking at it; I’ve read it so many times that I just don’t know, and I need other people whose opinions I value to look at it and say, this is where it needs to go. And I always find afterwards that it feels refreshing, that I’ve got a bit of a new perspective so I can go in and make adjustments. I do find it extremely valuable. And aside from that, just to have other people to talk about writing with: to be able to see what everybody else is doing and where their creativity’s taking them. To be able to talk about poetry and about stories with other people gets you out of your head a little bit. So, your poem “Backstitch” begins: "The subtle wrongness of this house is grinning in the windows.” We talked a bit about how poems come about; I wonder if we could talk for a minute about opening lines. That one is particularly stunning. Thank you. |